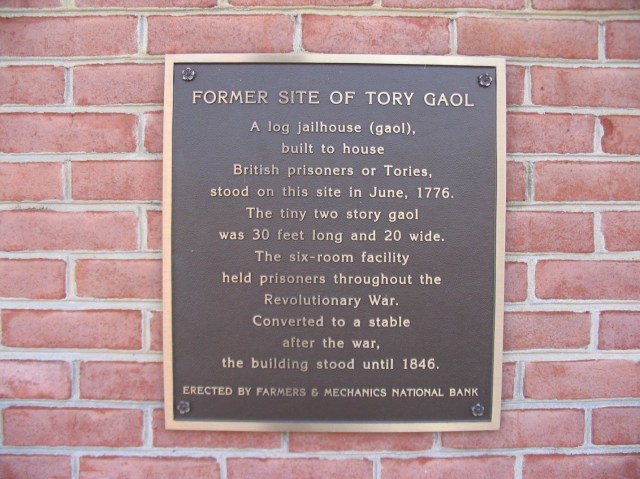

The first post in this series looked at the various prisons established in Frederick, Maryland to hold British, German, and Loyalist prisoners. We’ll wrap this up by examining a notorious trial that took place in 1781.

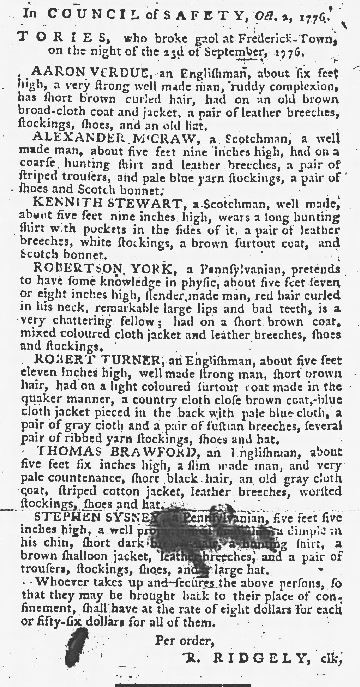

Perhaps the most well-known case involving Loyalist prisoners in Frederick occurred in the summer of 1781. By this point in the war, enthusiasm for the American cause was on the wane in many communities. Conscription and heavy taxation to support the war effort were unpopular, especially as there was little battlefield success to boost morale. British forces were campaigning deep in Virginia and the Carolinas, giving hope to local Loyalists. Some Loyalists chose to declare their allegiance publicly, leading to a number of short-lived “uprisings” against American rule.[i] The Council of Maryland got wind of one such conspiracy in June, 1781, when orders were given to the lieutenants of the Frederick and Washington County militias to arrest a number of “disaffected and Dangerous Persons whose going at Large may be detrimental to the State.”[ii] Among those singled out for arrest were “Henry Newcomer and Bleachy of Washington County and Fritchy, Kelly, and Tinckles of Frederick County.” All these men had been connected to a supposed plot to raise a group of armed Loyalists in western Maryland, free the prisoners of war in Frederick, and march to support Lord Cornwallis in Virginia.

The details of the plot were uncovered by Christian Orendorff, an enterprising militia captain from the vicinity of Sharpsburg, in Washington County. His neighbor, Henry Newcomber, had confided to him one night that “we have raised a body of men for the Service of the King” to be commanded by a “Dutch Man” from Frederick named Fritchey. Orendorff feigned sympathy with Newcomber’s cause and soon met with Caspar Fritchey, who revealed more of the plot to him – including names of some of his co-conspirators. Captain Orendorff sent word to the authorities, who acted quickly to break up the insurrection and round up the ringleaders. Although Orendorff claimed that the Loyalists had recruited 6,000 men, only seven were brought to trial.

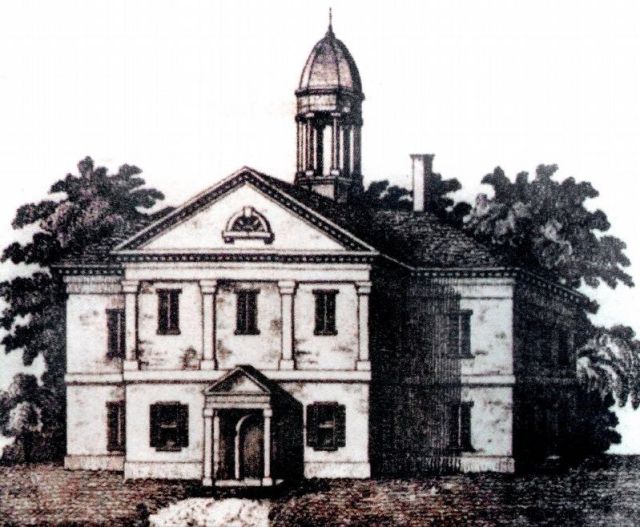

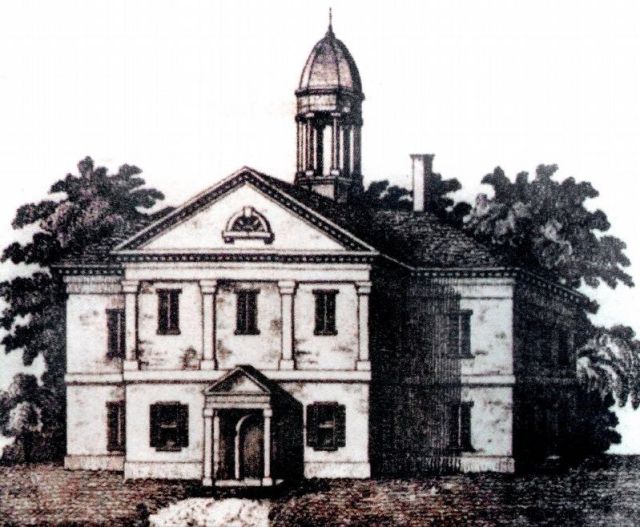

Frederick’s 1752 Courthouse as depicted on the 1858 Isaac Bond Map. The Courthouse burned in 1861 and was replaced the following year. The former courthouse now serves as city hall. (Library of Congress)

Frederick’s 1752 Courthouse as depicted on the 1858 Isaac Bond Map. The Courthouse burned in 1861 and was replaced the following year. The former courthouse now serves as city hall. (Library of Congress)

The seven men condemned to stand trial – Peter Sueman, Nicholas Andrews, John Graves, Yost Plecker, Adam Graves, Henry Shell, and Caspar Fritchie[iii] – were singled out as the leaders of the plot. All were brought to Frederick under a heavy guard while a special court convened. Thomas Sprigg, serving as Lieutenant of Washington County, wrote to the Council that “[they Acknowledge themselves to be Captains that they have Misted and Admin’d the Oath of Allegeance to many persons, one of them to the Amot of 42 they Confess very freely they say they expect and deserve to be hang’d, and I pray God they may not be disappoint’d…”[iv]

On June 17th, 1781 a special court of oyer and terminer was called. Derived from old English law, these special courts were overseen by a panel of commissioners, and typically presided over serious crimes like treason. Among the judges were the local militia commander Col. James Johnson, Alexander Hanson (son of President of the Continental Congress, John Hanson), and Upton Sheredine. All were men with staunch patriot sympathies. It wasn’t a surprise, then, that the trial was a short one. Relying primarily on Orendorff’s testimony, the court found all seven men guilty of treason against the state of Maryland. For the crime of enlisting men for the service of the King, Judge Hanson handed down a grisly punishment:

“You, Peter Sueman, Nicholas Andrews, Yost Plecker, Adam

Graves, Henry Shell, John George Graves, and Casper Fritchie,

and each of you, attend to your sentence. You shall be carried

to the gaol of Fredericktown, and be hanged therein; you shall

be cut down to the earth alive, and your entrails shall be taken

out and burnt while you are yet alive, your heads shall be cut off,

your body shall be divided into four parts, and your heads and

quarters shall be placed where his excellency the Governor

shall appoint. So Lord have mercy upon your poor souls.”[v]

Four of the accused – Andrews, Shell, and the Graves brothers – were subsequently pardoned due to their “want of education and experience.” It appears that the court saw them as young men duped by the real leaders of the plot. The other three men were not so lucky.

The former courthouse square in Frederick, near where the county jail once stood. It’s likely that the executions took place very near this location in August 1781. The large brick structure is the 1862 courthouse (now Frederick’s City Hall).

The former courthouse square in Frederick, near where the county jail once stood. It’s likely that the executions took place very near this location in August 1781. The large brick structure is the 1862 courthouse (now Frederick’s City Hall).

While the plot and trial are well documented, the aftermath is not. Later historians cannot agree on whether the entire sentence of hanging, drawing, and quartering was ever carried out, or if the three men were simply hung. On August 28, 1781 the Baltimore Advertiser simply reported that “On Friday the 17th instant, Caspar Fritichie, Peter Sueman, and Yost Plecker, suffered Death in Frederick Town for High Treason.” Many family stories that have been passed down in the area, however, firmly state that the full punishment was meted out on the unlucky Loyalists. Today the only physical reminder of this “First American Civil War” in Frederick is a simple bronze plaque and a small sign near the courthouse where the executions likely took place. The episode, however, still sheds light on the darker side of Maryland’s Revolutionary story.

[i] A perfect example was “Claypool’s Rebellion” on the Virginia frontier. In June 1781 John Claypool of Hampshire County, Virginia led a large body of men in resisting efforts to tax or raise troops for the State of Virginia. After dozens of men took up arms alongside Claypool a body of militia was sent to put down the “rebellion.” For more information visit https://secondvirginia.wordpress.com/2015/06/17/claypools-rebellion/

[ii] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1780-1781. p 467

[iii] John Caspar Fritchie was the father-in-law of legendary Civil War heroine Barbara Fritchie

[iv] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781. p 298

[v] Scharf. P 143

Frederick’s 1752 Courthouse as depicted on the 1858 Isaac Bond Map. The Courthouse burned in 1861 and was replaced the following year. The former courthouse now serves as city hall. (Library of Congress)

Frederick’s 1752 Courthouse as depicted on the 1858 Isaac Bond Map. The Courthouse burned in 1861 and was replaced the following year. The former courthouse now serves as city hall. (Library of Congress) The former courthouse square in Frederick, near where the county jail once stood. It’s likely that the executions took place very near this location in August 1781. The large brick structure is the 1862 courthouse (now Frederick’s City Hall).

The former courthouse square in Frederick, near where the county jail once stood. It’s likely that the executions took place very near this location in August 1781. The large brick structure is the 1862 courthouse (now Frederick’s City Hall).