Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes historian and educator Jeffrey Collin Wilford to the blog. A brief biog is at the bottom of this post. A list of sources will be at the bottom of the concluding Part III.

Major John André and John Van Dyk: Continental Artillery Soldier

Much has been written about the betrayal of America by Benedict Arnold. However, one small but candidly morbid fact buried in the story has not. It relates to the disposition of British Major John André’s remains as they lay in a wooden ossuary on a British mail ship on the banks of the Hudson River while awaiting their return to England in 1821. The only recorded recollection of this event was in a letter written by a 67-year-old former Revolutionary War soldier and published in a Virginia newspaper in 1825. This man also happened to be one of the four officers who escorted André to the gallows in Tappan, New York, on October 2, 1780.

John Van Dyk lived a storied life, serving America as a militiaman, Continental Artillery soldier, customs officer, New York City assessor, and assistant alderman. He came from an old Dutch family that had settled in the original New Amsterdam colony, which would eventually become Manhattan. There is ample evidence that, in 1775, he was actively involved in significant acts of disobedience against British rule with other “Liberty Boys,” as the New York Sons of Liberty preferred to call themselves.

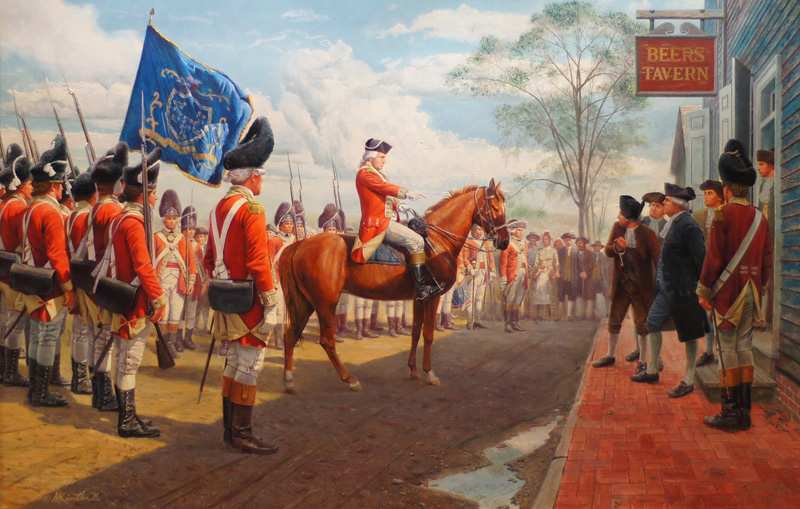

One of these acts was stealing muskets and cannons from the Royal Armory and Fort George. Under the encouragement of Isaac Sears and Marinus Willett, he was one of a crowd of colonists who broke into the Royal Arsenal at City Hall on April 23, 1775, stealing 550 muskets, bayonets, and related munitions. The angry mob had been spurred to act by the attacks on their fellow countrymen the week previous at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. Every person who took a musket was required to sign for it, signaling a promise to return it if it was needed to fight against British occupation. That call came on July 4, 1775, when the New York Provincial Congress ordered them recalled to outfit newly commissioned Colonel Alexander McDougall’s 1st New York Regiment. It was relayed that anyone who refused would be deemed an enemy of the state. In all, 434 muskets were returned.

Exactly four months later, Captain John Van Dyk was one of sixty or so men who, under Liberty Boys Colonel John Lasher and Colonel John Lamb, executed the orders of the New York Provincial Congress to remove the cannon from Fort George at the southern tip of Manhattan and drag them back to the area of City Hall. With tensions high in the city, the state leaders feared they would be turned against the colonists if they were left in the hands of the British. One of the militia members assisting in the removal effort was 19-year-old King’s College student Alexander Hamilton of the Hearts of Oak independent militia. By this time, civil unrest had relegated the British colonial government to operating from naval ships anchored in New York Harbor, which made keeping the cannon secure from a more agitated population nearly impossible.

Just before midnight on August 23, 1775, a skirmish ensued between Lasher and Lamb’s men removing the cannon, and a British barge near the shore. It had been sent to monitor the rebels’ activity by Captain George Vandeput from the HMS Asia, a 64-gun British warship anchored near shore. Musket shots rang out, presumably started by the British, which resulted in the killing of a King’s soldier on the barge. As a result, the Asia turned broadside and opened fire with their cannons in a barrage on the city that lasted for three hours. A city whose population had already been diminished by the fear of a coming conflict, shrunk even further due to the terror experienced that night.

John Van Dyk spent most of the next eight years as an officer in General Henry Knox’s artillery while under the command of Colonel John Lamb. During the war, he saw action at Brooklyn, Harlem Heights, White Plains, Trenton, Brandywine, Germantown, Crosswicks Creek, Monmouth, and Short Hills. He was also at both Morristown winter encampments and Valley Forge. In 1780 he was captured by the British off the coast of New Jersey and confined on the prison ship HMS Jersey in Brooklyn before being released that summer.

Van Dyk had spent months out of commission in late 1779 and early 1780 with what, according to his symptoms, was probably malaria or yellow fever. He petitioned General Knox, who, in turn, appealed to General Washington for leave to recuperate. Making his way to West Point to meet with General Washington he was instructed by the Commander-in-Chief’s aide-de-camp to be evaluated by Dr. John Cochran, physician and surgeon general of the army of the Middle Department. On Cochran’s recommendation, General Washington wrote to President Samuel Huntington asking that the Continental Congress grant Van Dyk’s petition for an 8-month Furlow to sea to convalesce, which was common at the time as it was believed the fresh sea air was helpful to healing. Approved, it would take six months before he boarded the brig General Reed with a crew of 120 and 16 guns, a privateer out of Philadelphia commanded by Samuel Davidson. Once aboard ship he was temporarily made a Lieutenant of Marines.

Only two days into the voyage, on April 21, 1780, things took an immediate turn for the worse when they were intercepted and captured by the 28-gun HMS Iris and the 16-gun sloop HMS Vulture. The Iris was the former American warship USS Hancock, captured in July of 1777 and renamed by the British. Van Dyk was brought to Brooklyn and placed on the prison ship Jersey in Wallabout Bay, one of the most notorious and deadly places for holding American prisoners of war. Conditions were so poor that, while approximately 6,800 American soldiers died in battle during the Revolution, over 11,000 prisoners died on the Jersey alone! Fortunately for John Van Dyk, American officers were often traded off the Jersey for British officers who were in the custody of American forces. Within two months he was released and traveled to his temporary home of Elizabethtown, New Jersey to finish recuperating before rejoining Lamb’s artillery in Tappan, New York.

John Van Dyk had experienced many horrors of war in the years and months leading up to the morning of September 21, 1780, when British Major John André, an Adjutant General to British General Sir Henry Clinton, left New York City and sailed up the Hudson River. This pivotal incident would brand one of Washington’s closest generals a traitor and lead to the death of the esteemed and well-liked André. Ironically, Major André traveled on the very same sloop that had assisted in the capture of Captain Van Dyk just six months earlier.

Bio:

Jeffrey Wilford has been an educator in Maine for over 30 years where he holds certifications in history and science. He received a bachelor’s degree in communications with an emphasis in journalism from California State University – Fullerton and a master’s degree in education, teaching and learning, from the University of Maine. In addition to his career teaching, he has worked as a general assignment newspaper reporter and an assistant to the press secretary of former Maine Governor and US Congressman Joseph Brennen. He lives in Maine with his wife Nicolette Rolde Wilford.