In honor of the 250th anniversary of the Battle of Quebec, we reshare guest historian Scott Patchan’s post on Daniel Morgan during the Canadian Campaign of 1775. This post originally posted in December 2015.

When the situation deteriorated to outright rebellion against the crown, Morgan raised a regiment of crack riflemen from Frederick County, and marched them to Boston in twenty-one days to take part in the siege of Boston. There, he served under his former commander from the French and Indian War, General George Washington. Morgan learned the hard way that orders must be followed. He once allowed his riflemen to exceed orders in firing upon British positions at Boston. Washington called Morgan on the disobedience, and Daniel thought that he would be cashiered from the army. Washington, however, relented the next day, but Morgan had learned a valuable lesson about following orders.

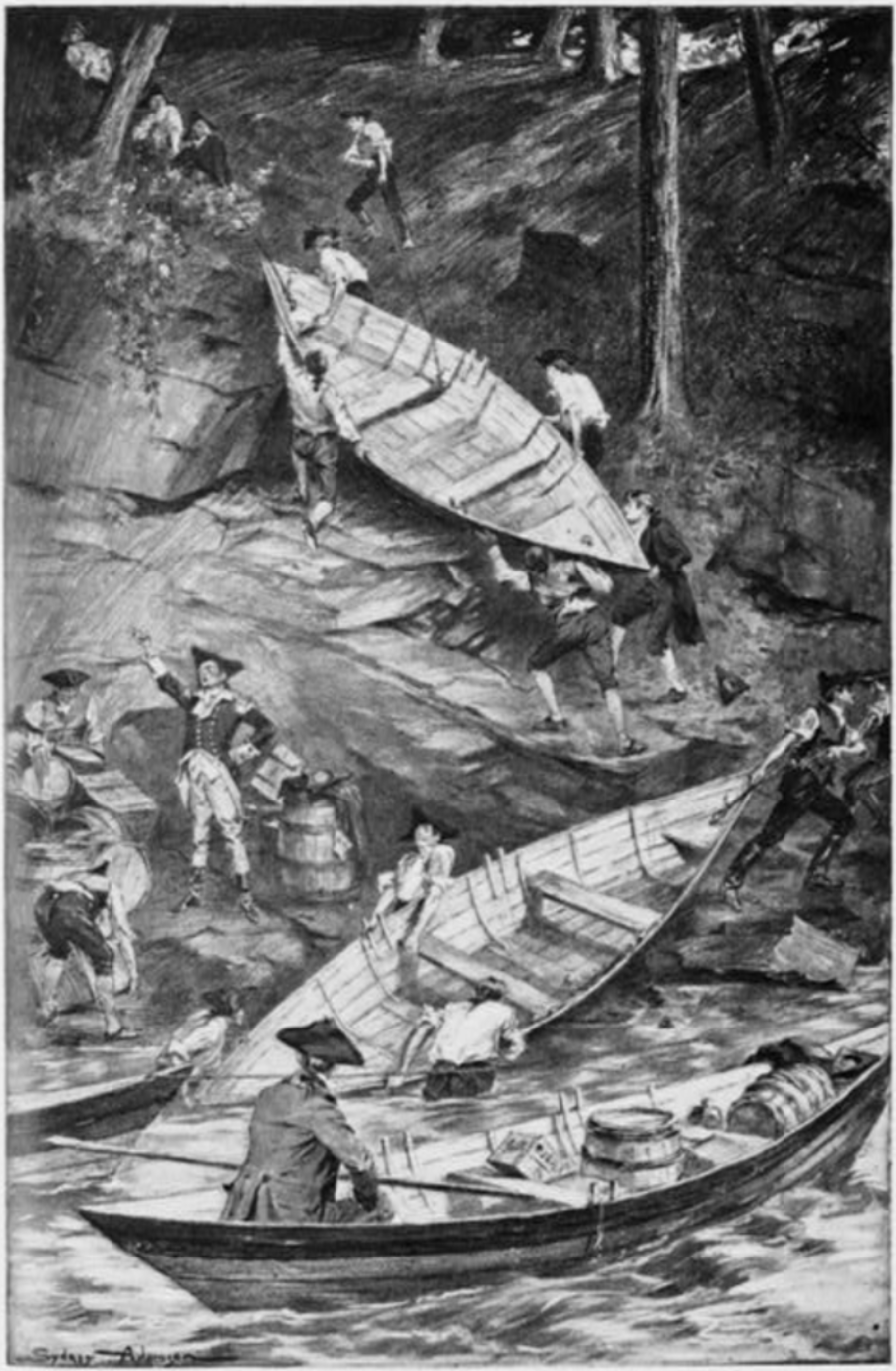

In the fall of 1775, Washington sent Morgan as commander of three companies of Continental riflemen on a mission to capture Quebec from the British. Morgan’s command marched with the column of Colonel Benedict Arnold. They traversed the Maine wilderness, rowing up stream to the “Great Carrying Place,” where carried their canoes and bateaux for great distances overland to another series of streams and lakes that took them to Quebec. As the cold weather set in, sickness and hunger overtook the column and Arnold sent those unfit for duty back to the rear. After covering 350 miles, the American arrived in front of Quebec in early November, surprising the British.

Although Morgan wanted to attack immediately and utilize the element of surprise, he was overruled and the small American force besieged Quebec, waiting for another column under General Richard Montgomery to arrive from the Hudson Valley. When a British party sallied forth and captured one of Morgan’s riflemen on November 18, Arnold believed the British would come out and fight in the open. As such, Arnold drew up his army in front of the fortifications to meet them. They declined his offer and instead looked down on the ragamuffin Americans from the ramparts and exchanged taunts and catcalls. The overall situation frustrated the irascible Morgan, and when his men complained that Arnold was not giving the riflemen their fair share of rations, the “Old Wagoner” violently argued with Arnold, and nearly came to blows with the future traitor. Morgan departed Arnold, leaving him with angry warning about poor treatment of the riflemen. From that time forward, Morgan’s command always received their fair share of the army’s rations.

Montgomery’s column arrived on December 5, and the Americans commenced setting up his mortars and artillery outside of Quebec. The Americans finally attacked during a snowstorm in the early morning darkness of December 31, but their force numbered only 950 men. Arnold’s column came under fire as it moved toward the ramparts of Quebec, and a musket ball struck Arnold taking him out of action. Although Morgan was not the senior officer, the others insisted that he take command, having seen actual combat which they had not. Morgan later noted that this “reflected credit on their judgment.” At Morgan’s order, his riflemen rushed to the front, armed with both their Pennsylvania rifles and a spontoon for the assault while some carried ladders to storm the walls. They quickly drove a small force of British away and closed in on the walls.

(courtesy of British Battles)

Morgan ordered the men up the ladders and first one gingerly began the climb. Morgan sensed his hesitancy, pulled him down and scaled it himself, shouting, “Now boys, Follow me!” The men instantly complied, and Morgan reached the top of the wall where a volley of musketry exploded, knocking him back to the snow-covered ground. The burst burnt his hair and blackened his face; one ball grazed his cheek and another pierced his hat; but Morgan was otherwise unhurt. Stunned he laid motionless on the ground for a moment, and the attack stopped, his men thinking him dead. But he soon stirred and clambered up the ladder to the cheers of his men who followed suit. This time he stopped before reaching the top, and hurtled himself over the rampart into the midst of the enemy. He landed on a cannon and injured his back and found British bayonets levelled at him from all directions. While the British focused on Morgan, his riflemen poured over the wall and came to his rescue, driving off Morgan’s would-be impalers. Morgan kept up a close pursuit of the British who offered weak resistance to the attacking riflemen. Although Morgan had broken into Quebec, the main body of Arnold’s division failed to follow the riflemen over the wall and exploit the opportunity at hand. Morgan captured much of the lower portion of Quebec with only two companies of his riflemen. He later described the breakdown that occurred:

“Here, I was ordered to wait for General Montgomery, and a fatal order it was. It prevented me from taking the garrison, as I had already captured half of the town. The sally port through the (second) barrier was standing open; the guard had left it, and the people were running from the upper town in whole platoons, giving themselves up as prisoners to get out of the way of the confusion which might shortly ensue. I went up to the edge of the upper town with an interpreter to see what was going on, as the firing had ceased. Finding no person in arms at all, I returned and called a council of war of what few officers I had with me; for the greater part of our force had missed their way, and had not got into the town. Here I was overruled by sound judgment and good reasoning. It was said in the first place that if I went on I should break orders; in the next, that I had more prisoners than I had men; and that if I left them they might break out and retake the battery we had just captured and cut off our retreat. It was further urged that Gen. Montgomery was coming down along the shore of the St Lawrence, and would join us in a few minutes; and that we were sure of conquest if we acted with caution and prudence. To these good reasons I gave up my own original opinion, and lost the town.”

Montgomery never arrived; he had been killed in the first blast of musketry against his column, and his command broke. As time went on, the British regained their composure and pushed back against Morgan’s command. Morgan went back and brought up 200 New Englanders who joined the riflemen as they attempted to renew the attack. Now, the previously undefended point, was well manned, and daylight illuminated the paucity of Morgan’s numbers. Nevertheless, Morgan pressed them back further into the town to an interior fortification. A brave British officer led a counterattack, but Morgan personally shot him dead and disrupted the assault. Nevertheless, the time for action had passed. The British had become aware that Morgan’s was the only active American force in the city and closed in around him. In the meanwhile, additional British forces reoccupied the gates Morgan had initially taken and trapped him in the city. Morgan had no choice but to surrender his small command.

(courtesy of British Battles)

Morgan and the other officers enjoyed a liberal captivity with generous quarters in a seminary. The British officers visited them often and remained on friendly terms with the Americans. Morgan developed a dislike for some of his fellow officers whom he regarded as dishonest and scheming, and his fighting skills were brought to bear on at least one occasion when several men teamed up against big Dan Morgan. The imprisonment ended when the British returned the American officers on September 24, 1776, in New Jersey. Morgan returned to his wife and two daughters at his home outside of Battletown or Berryville, where he awaited his proper exchange. While there, he named his home “Soldier’s Rest,” as he recuperated from the trials of the taxing expedition to Quebec. The war was still young, and the Continental Army would soon be calling upon his services again. A special command of riflemen was being organized and Morgan would be its commander.