Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian Madeline Feierstein to the blog. A bio follows the article.

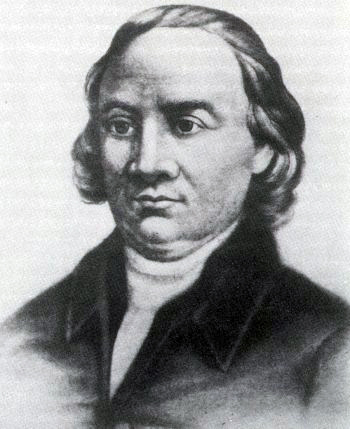

John Morton (1725-1777) had a storied political career. From election to the Pennsylvania Assembly at the prime age of 31, he soared to his state’s delegation at the First and Second Continental Congress. It is made even more astounding by the fact that he is the only Founding Father with roots in New Sweden. While his political activities and civic service are well-documented, one wonders if his personal identity and family traditions left a lasting impact.

New Sweden was the Kingdom of Sweden’s attempt at a colonial settlement in the “New World.” Situated along the Delaware River, it was difficult to entice enough settlers to relocate to this wilderness. Despite its eventual absorption into the Dutch colony of New Netherland, its Swedes and Finns left behind an enduring legacy: the log cabin.

John Morton’s great-grandfather, under the original Swedish Mårtenson/Finnish Marttinen, emigrated to New Sweden in 1654. His father died the year John was born (1725), and his mother passed the same year that he died (1777).[1] Stepfather John Sketchley, a land surveyor of English extraction, appeared to have much influence on young John’s life and career. Morton married fellow Finnish heritage descendant Anne Justis and the couple had eight children who lived to adulthood. Researchers debated whether Morton knew of his Finnish roots, or if he self-identified as solely Swedish.[2] The historic high concentration of ethnic Finns alongside Swedes in the Delaware River Valley, combined with their efforts to preserve traditions, can lead one to believe that he had significant exposure to his roots – if not by his neighbors then through his wife.

By the time independence was on the table in Philadelphia, Morton had represented Pennsylvania as a native son for decades. As a descendant of New Sweden, however, his lineage predates William Penn’s control of the colony in 1681. Due to New Sweden’s brief dominance of the area, much of the original settlers’ foundations in the state have been claimed for Penn. The work of the Swedish Colonial Society and the American Swedish Museum revolves around educating on the existence and imprint of this culture on the American landscape.

Pennsylvania hotly debated the topic of independence from Great Britain. Morton saw both sides to the argument but cautiously supported disunion, believing that this division would “heal wounds” aggravated against his state by tyrannical rule. [3] Morton himself has been dubbed the “tie breaker,” due to his deciding vote – which carried his state and the rest of the Congress in favor of separation. His signatures lies under that of another famed Pennsylvanian: Benjamin Franklin.

As an American, Morton helped craft the Articles of Confederation. Sadly, he did not see his new nation come to fruition. Morton also has the accolade of being the first Founding Father to die. Passing from a lung condition (likely tuberculosis), his grave in Chester, Pennsylvania remained unmarked until an obelisk was installed by his descendants in 1845. No mention of his New Sweden roots are noted on the gravesite or monument.

While his name is etched into history as the anglicized John Morton, his familial homestead stands at Prospect Park, where a collection of New Sweden’s history has been carefully preserved. More strides have been made internationally, with Morton continuing to act as a cultural and diplomatic link between his ancestral lands and the United States. In Finland, the U.S. Embassy named a prominent room after John Morton, as well as the University of Turku with its John Morton Center for North American Studies.

[1] Edward Root, MD, “Commemoration of John Morton,” The Swedish Colonial Society Journal, vol. 5: 7, Fall 2017, https://colonialswedes.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/SCSJ_vol5_no7.pdf

[2] Auvo Kostianien, “The Genealogy of John Morton, the Signer: the DNA Results,” Migration-Muuttoliike Journal, vol. 47: 2, 2021, https://siirtolaisuus-migration.journal.fi/article/view/109443/64279

[3] Richard Stromberg, “John Morton,” Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, 2007, https://www.dsdi1776.com/signer/john-morton/

Bio:

Madeline Feierstein is an Alexandria, VA historian and founder of the educational and historical consulting company Rooted in Place, LLC. A native of Washington, D.C., her work has been showcased across the Capital Region. Madeline is a writer for Emerging Civil War and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. She leads significant projects to document the sick, injured, and imprisoned soldiers that passed through Civil War Alexandria. Madeline holds a Bachelor of Science in Criminology from George Mason University and a Master’s in American History from Southern New Hampshire University. Explore her research at www.madelinefeierstein.com.