If not for his connections to some of the most famous commanders and events of 18th-century military history, British general Charles O’Hara might only get a passing mention in many history books. He still hardly gets more than that.

Charles O’Hara came into this world unceremoniously as the illegitimate son of James O’Hara, a British baron. The younger O’Hara cut his teeth in military matters at the young age of 12 in the 3rd Dragoons before receiving an officer’s appointment in the Coldstream Guards. He served in an officer’s capacity in Germany, Portugal (with Charles Lee), and Africa. O’Hara was strict but liked by the men who served under him.

O’Hara’s years of military service brought him to North America in July 1778. Lieutenant General Henry Clinton appointed him to command the troops at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, to protect New York City because of his engineering skills and a recommendation from Admiral Richard Howe. Two years later, O’Hara wound up under the command of Lord Charles Cornwallis in the Southern theater. He performed ably there, leading the pursuit of Cornwallis’ army toward the Dan River in early 1781 and leading the British counterattack at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. O’Hara led from the front and received two wounds to show for it. His nephew died during the battle.

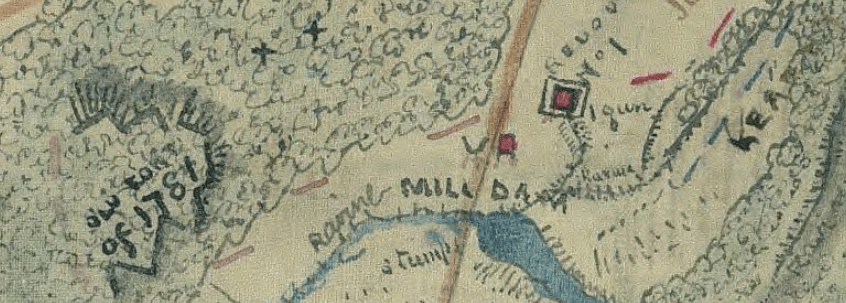

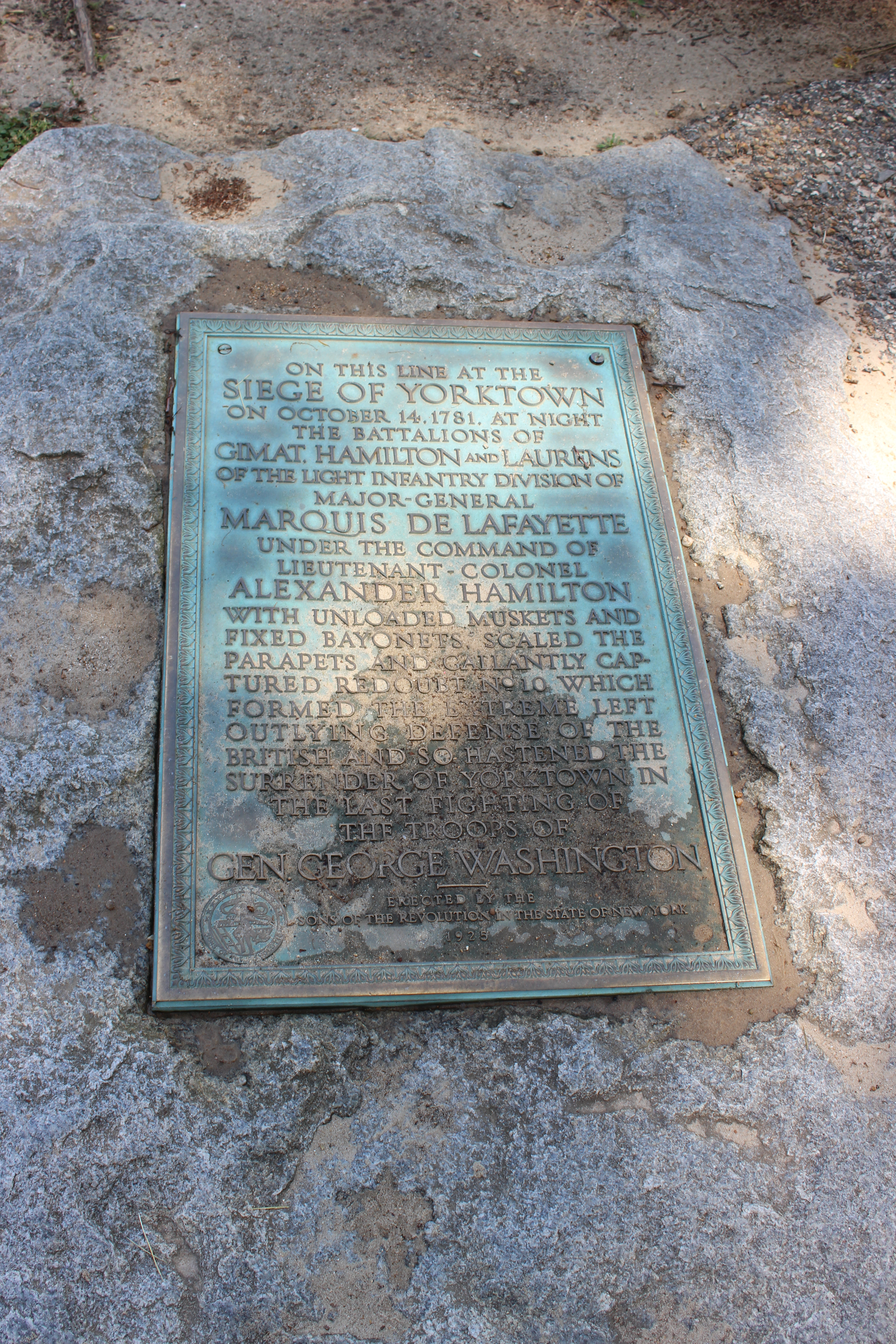

At Yorktown, O’Hara drew the duty of surrendering Cornwallis’ army to General George Washington and Comte de Rochambeau. As the surrendering British columns approached the Allied lines, O’Hara asked to see Rochambeau. Whether this was a slight against Washington or not is unclear, but Rochambeau referred him to Washington. O’Hara apologized to Washington and explained why Cornwalls was not in attendance. Then, O’Hara handed Cornwallis’ sword to Washington, who refused it and passed O’Hara along to Benjamin Lincoln. O’Hara handed the sword to Lincoln. He looked it over, held it for a brief moment, and returned it to O’Hara. The surrender of the British army then began.

After dining with Washington following the surrender proceedings at Yorktown, O’Hara became Washington’s prisoner until receiving his exchange on February 9, 1782. He returned to England with Cornwallis’ praise and a promotion to major general. Back home in England, O’Hara fell into hard financial times from a gambling debt and ran away from them to mainland Europe. In stepped his old friend and commander Charles Cornwallis, who helped O’Hara offset the debts.

O’Hara received another promotion in 1792 to lieutenant general and lieutenant governor of Gibraltar, a post he long desired. There, misfortune found him once more when he faced the young Napoleon Bonaparte on the battlefield of Toulon. On November 23, 1793, the defeated O’Hara surrendered to Napoleon.

Labeled an insurrectionist, O’Hara found himself in prison in Luxembourg. During his nearly two years there, he befriended American Thomas Paine until his exchange in August 1795. Ironically, the man exchanged for him was the Comte de Rochambeau. He once again took the post of Governor of Gibraltar, where he died in 1802 from the effects of his war wounds suffered two decades earlier.

Despite taking part in one of the most famous events of the Revolutionary War, O’Hara has faded into general obscurity even though he bears the distinction of being the only person to surrender to both Washington and Napoleon.

He is featured regularly on the screen in The Patriot, but most people likely do not even know the character’s name or backstory. There is plenty more to be told in his story.