Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Malanna Henderson

Part One

“It is not for their own land they fought, not even for a land which had adopted them, but for a land which had enslaved them, and whose laws, even in freedom, oftener oppressed than protected. Bravery, under such circumstances, has a peculiar beauty and merit.” – Harriet Beecher Stowe.

The words spoken by “the little woman who wrote the book that started this Great War,” so said Abraham Lincoln, according to legend, upon meeting Mrs. Stowe sometime in 1862, rang true for black patriots in the Civil War as well as those in the Revolutionary War.

The Smithsonian tome, The American Revolutionary War: A Visual History quotes a Hessian officer in 1777, as saying, “No regiment is to be seen in which there are not Negroes in abundance and among them are able-bodied and strong fellows.”

In every battle of the Revolutionary War from Lexington to Yorktown; black men, slave and free, picked up the musket and defended America; and yet, many historians as well as visual artists have omitted their contributions in the history books and their images on canvases depicting historic battles. The need for white historians to “overlook,” “underestimate,” and or “erase,” these sacrifices is a gross negligence that distorts and misrepresents American history; and furthermore, it continues to disenfranchise the patriotic heroes of the past and malign the self-image of millions of Americans today simply because of the color of their skin.

Black soldiers have always fought two wars simultaneously; wars declared by their government and the unspoken wars at home for liberty, equality and before the Civil War, for citizenship.

What kind of men fight for the liberty of others when their own liberty isn’t guaranteed?

True patriots: James Armistead Lafayette was one such person.

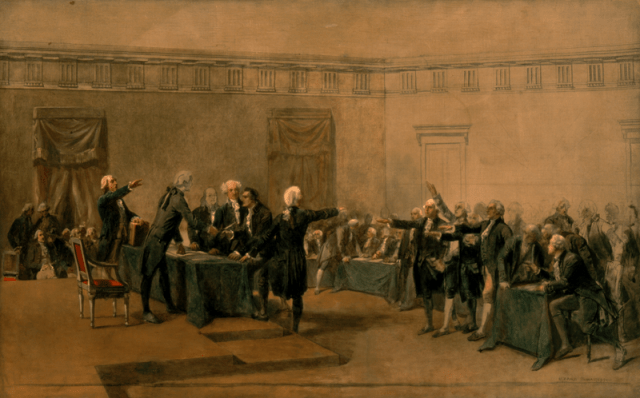

Slaves serving in the rebel military was a question that manifested itself early amongst the colonial government agencies. Their presence rankled many, while others welcomed them and praised their bravery. Some men of color had fought gallantly and with distinction as they stood alongside their white compatriots, defenders of liberty on the Lexington Green in April of 1775.

For instance, in the Battle of Bunker Hill, Peter Salem, a slave, served with courage under fire, as varying accounts reported. Salem was introduced to George Washington as “the man who shot Pitcairn,” the British Royal Marine Major who shouted to his men before Salem shot him down, “The day is ours.” Despite the competence and bravery of such men on the battlefield their exploits didn’t convert the wide-spread reluctance of most colonists to accept black men as soldiers.

General George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, harbored the same common prejudices of the southern-planter ruling class of which he was a member. In July, he instructed recruiters “not to enlist any stroller, negro, or vagabond, or person suspected of being an enemy to the liberty of America.” Commanders in each colony and regiment made up their own minds. Some ignored his command. Their decision was based on need and experience. Those who had already served successfully with black militia and minutemen may have seen no cause to alter their regiments.

By December of 1776, Washington back-pedaled on his decision, allowing for black veterans of Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill to serve; but of the slave, he maintained his objection. However, some junior officers appreciated the contributions of blacks. Col. John Thomas wrote John Adams on October 24, 1775, “We have negroes, but I look upon them as equally serviceable with other men, for fatigue (labor); and, in action many of them have proven themselves brave.”

As the war raged on, the necessity for able-bodied men settled the question. White soldiers, who usually served for only a few months to a year, mustered out, died or were wounded; while others deserted. Black soldiers who expected to receive their freedom if they served were in the war for the duration. This was a positive factor for the commanding officers who had to re-train all new recruits. Around five-thousand blacks served in the Revolutionary War as soldiers. However, a vast unknown number provided a myriad of support services.

Another reason the colonials reconsidered enlisting blacks was the bold military tactic that occurred in November of 1775. Lord Dunmore, the last royal governor of Virginia, ratified a proclamation freeing all indentured servants and slaves of rebels if they would fight for the British. Thousands of people fled the plantations to gain their freedom. This single act struck a devastating blow on two fronts, it threaten their economic stability and increased the tension between master and slave, with the master fearing slave revolts and the permanent loss of their property. Moreover, it upset the social order. Enslaved men serving alongside whites put them on an equal footing in the battlefield, which violated the white supremacy dogma that governed current thought and practice.

Born into slavery on December 10, 1748, in New Kent, Virginia to owner William Armistead, James enlisted in the Revolutionary War under General Marquis de Lafayette in 1781. His owner was a patriot and most likely received the bonus James would have gotten for enlisting had he been free or white. Enlistment bonuses comprised of money, land or slaves.

By the time Armistead entered the war, the efforts of Benjamin Franklin and other colonial agents had secured a military and economic alliance with the French. A long-time imperial rival of British expansion, the French provided naval ships, money and personnel.

Marquis de Lafayette (born Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier) was a descendant of ancient French nobility. His father, a colonel in the French Grenadiers had died in the Seven Year’s War (known as the French and Indian War in America) when the young nobleman was only two years old. The political ideals of liberty and equality espoused by the colonials matched his beliefs and fired his military ambitions. Perchance, his yearning to play a role in America’s fight for independence from British rule may have been spawned by a desire to avenge his father’s death.

Since Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, it was easy for Armistead to gain access in the enemy camps as a runaway slave seeking his freedom. While providing varied services to the British, he gained the confidence of Brigadier General Benedict Arnold, who by now had defected to the British. He charged Armistead with scouting, foraging and spying. Armistead was able to comfortably go between both camps, in essence becoming a double spy. He carried false and misleading information to the British but provided accurate intelligence on the movement of British forces and details of their military strategies to General Lafayette.

When Arnold left Virginia, Armistead was able to deceive General Charles Cornwallis as well, who rampaged through parts of Virginia and burned Richmond, the capital. He sent Colonel Banastre Tarleton to capture the entire legislative assembly, which included Daniel Boone, Patrick Henry and the governor. The plan was thwarted by an astute young man named Jack Jouett. Although, a few were apprehended, among them Daniel Boone; Jouett’s actions prevented the British from arresting the biggest prize: Governor Thomas Jefferson.

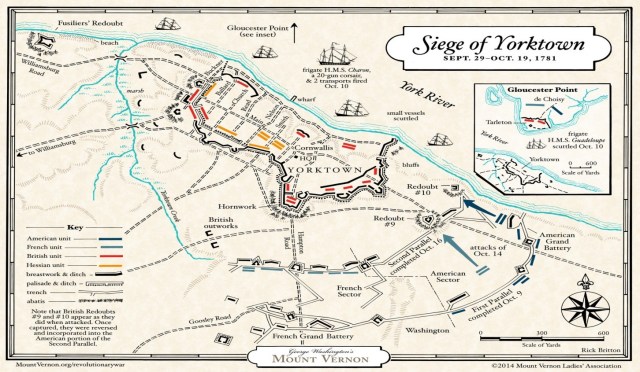

By early August, Cornwallis had made plans to establish fortifications in Yorktown, expecting reinforcements to increase his troops of approximately nine-thousand.

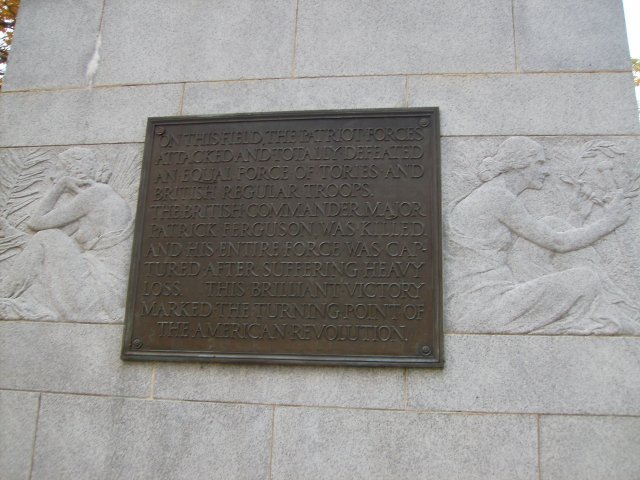

General Washington, in the meantime, had joined forces with Comte de Rochambeau to recapture New York. With intelligence supplied by James Armistead, they learned that Cornwallis was in Yorktown waiting for military support. French Admiral de Grasse, with a fleet of about twenty-eight naval ships, was on his way to the Chesapeake from St. Dominick (present-day Haiti). A plan to surround Cornwallis by land and sea appeared possible. The French naval fleet, along with the Washington’s Continental and Rochambeau’s French forces, headed to the enemy’s headquarters. Once Washington reached Yorktown, General Lafayette’s regiment joined him. Thus, Armistead’s accurate and meticulous reports were vital to the American victory that culminated in Yorktown on October 19, 1781.

Later Cornwallis met the Marquis at his headquarters and was flabbergasted to find his spy James Armistead present.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 severed ties from Britain, the mother country, and established America as an independent nation. That same year, the Act of 1783 was passed freeing slaves who had fought in the Revolutionary War on their masters’ behalf. However, it excluded slave-spies. Ergo, James Armistead, who risked his life by providing information to help win the freedom of many, was himself denied freedom. Was his life in less danger operating under subterfuge as a spy amongst the British than it would have been, had he served as a soldier on the battlefield? I think not. Had his espionage been discovered, he surely would have had to forfeit his life.

After the war, Armistead was returned to slavery. Even his own master didn’t have the legal right to free him because of the Act of 1783, omitting slave-spies from emancipation.

When learning of his compatriot’s status, the Marquis penned a certificate to the Virginia legislator in October of 1784 imploring them to grant Armistead his freedom, declaring:

“This is to Certify that the Bearer By the Name of James Armistead Has done Essential Services to me While I had the Honour to Command in this State. His Intelligences from the Ennemy’s Camp were Industriously Collected and More faithfully deliver’d. He properly Acquitted Himself with Some Important Commissions I Gave Him and Appears to me Entitled to Every Reward his Situation Can Admit of. Done Under my Hand,” Richmond, November 21st 1784.

The legislator didn’t act upon the request straightaway. However, again in 1786, James Armistead applied for his freedom and it was duly granted on January 9, 1787, with a fair compensation to his master, William.

In honor of his benefactor, James Armistead added Lafayette to his surname. After emancipation, he moved a short distance south of New Kent, near Richmond, Virginia and acquired forty acres of less than suitable farmland. He married and had a family. He even owned slaves. History doesn’t tell us if he bought enslaved relatives to free them or if they were bought to farm his land as field hands.

It wasn’t until 1819 that he applied to the state legislature for financial assistance to ease his poverty. This time, the response was immediate; he received $60 and an annual pension of $40 for his service during the Revolutionary War.

Unlike James Armistead Lafayette, many blacks who worked as laborers, guides, messengers and spies were not as fortunate. Whether they were pressed into service or willingly answered the call, most neither received their freedom nor wages for their behind-the-scene contributions to the war.

In 1824, the Marquis de Lafayette visited the United States and was lauded as a hero of the American Revolutionary War in Richmond with festivities and a parade. Spying Armistead in the crowd, it is said he halted the procession, dismounted from his horse and embraced his old comrade.

_____________________________________________________________

End Notes

References:

- Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Alan Steinberg Black Profiles in Courage: A Legacy of African-American Achievement. (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.1996) pages 32-34.

- Jamestown & American Revolutionary War, “Marquis de Lafayette” http://www.historyisfun.org/learn/learning-center/colonial-america-american-revolution-learning-resources

- “James Armistead Lafayette – Hero and Spy”. http://www.historyisfun.org/blog/james-armistead-lafayette

- Col. Michael Lee Lanning (Ret.) Defenders of Liberty: African Americans in the Revolutionary War. (New York: Kensington Publishing Corp. 2000) pages 45-46; 130

- Journal of the American Revolution “Marquis de Lafayette, European Friend of the American Revolution”. https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/05/the-marquis-de-lafayette-european-friend-of-the-american-revolution/

- “James Armistead Biography. http://www.biography.com/people/james-armistead-537566#synopsis

- Smithsonian The American Revolution, A Pictorial History. (New York: DK Publishing, First Edition 2016)

- Harry M. Ward, For Virginia and For Independence: Twenty-Eight Revolutionary War Soldiers from the Old Dominion, Chapter 26 “Spy”, pages 155-159.