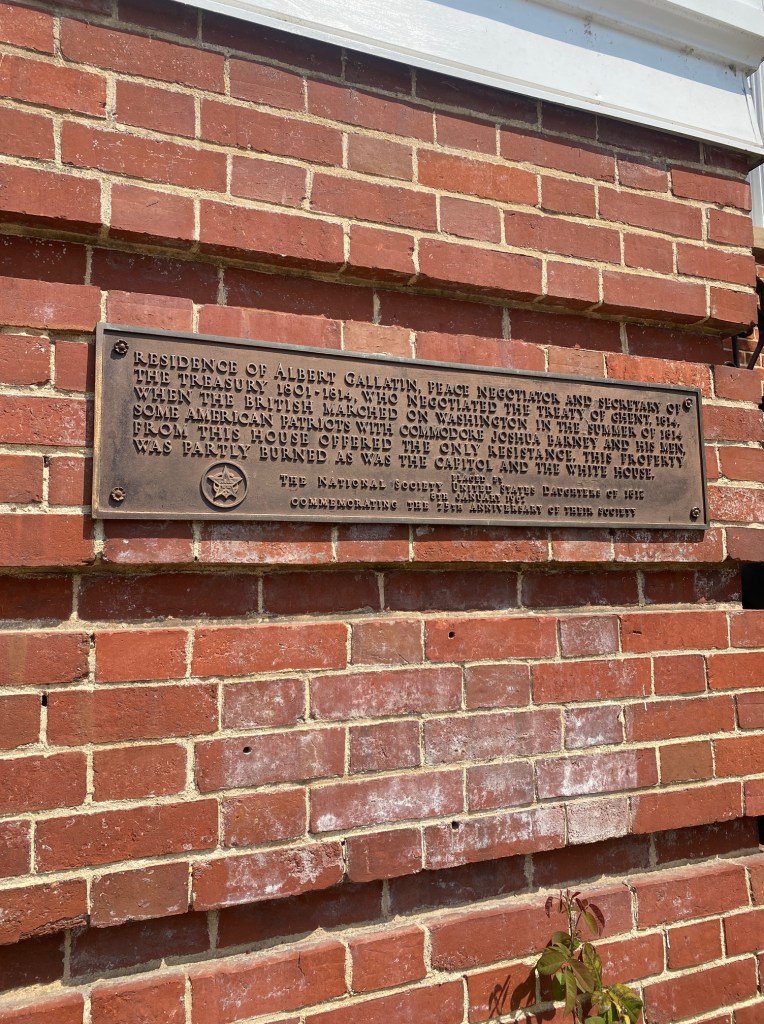

Not long ago, a good friend of mine found himself in Henry County, Va. Located southwest of Richmond, the county was named for the patriot, Patrick Henry, in 1777. Touring a local cemetery there, my friend came upon a very interesting headstone. It was the grave marker for a soldier of the American Revolution; a man named Thomas Pearson.

According to the headstone, Thomas Pearson had served in the Virginia Continental Line and in May 1780, was wounded in battle against the British in South Carolina. My friend sent me a photograph of the headstone. Based on the place and date, he was hoping this Thomas Pearson had perhaps served at the battle of Camden. As a co-author of a book on Camden, I have to admit that I was quite intrigued myself.

But, based on my research for the book, I knew immediately that certain pieces of information on the man’s epitaph didn’t correspond to details of the Camden fight. First off, it indicates that Thomas Pearson served in the Virginia Continental Line. The Virginians engaged at Camden were actually not part of the Continental Line but, rather, state militia forces commanded by Gen. Edward Stevens. In fact, most of the troops of the Virginia Continental Line were captured by the British at the fall of Charleston on May 12, 1780.

The epitaph also reads that Pearson was wounded in May 1780, in South Carolina. The battle of Camden occurred later, on August 16, so most likely this gentleman wasn’t there. Still, the gravestone intrigued me. I decided to do a little research into Thomas Pearson and sadly, I was to discover that his story was a tragic one.

On November 30, 1812, at the age of 61, Thomas Pearson applied for a pension for his services in the Revolutionary War from the Commonwealth of Virginia. According to his application, he was “a soldier in the revolutionary war, belonging to the VA Line on continental establishment, and attached to the regiment commanded by Col. Abraham Buford.” Clearly, he was a veteran of the southern campaign.

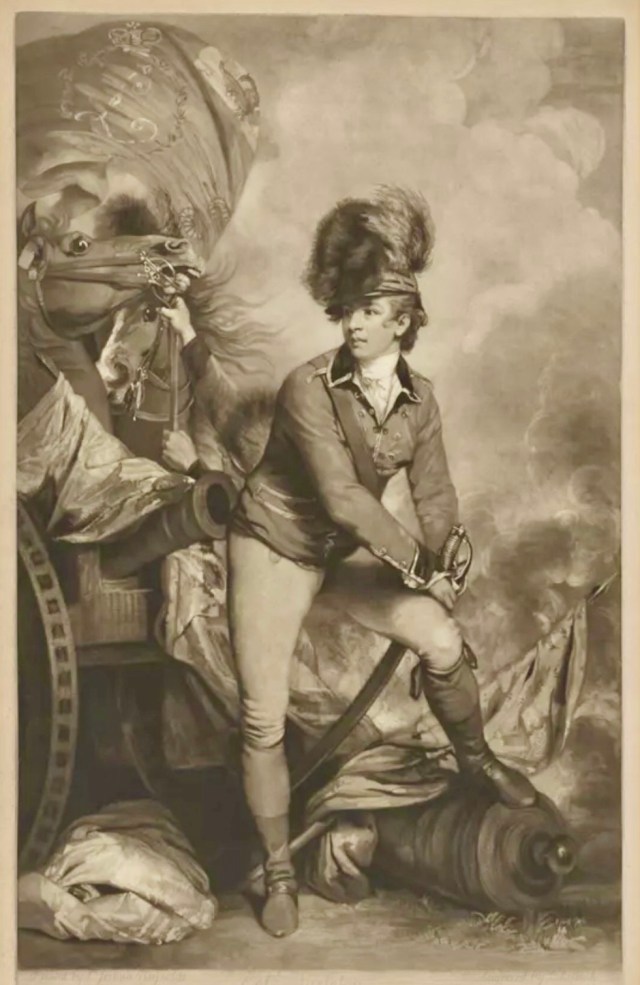

In May 1780, he was indeed serving in the Virginia Continental Line, as an officer of the 3rd Virginia Detachment of Scott’s Virginia Brigade. Commanded by Col. Abraham Buford of Culpepper County, VA, the 3rd Detachment, nearly 400 strong, was marching into South Carolina to the relief of the City of Charleston, which was under siege by the British. The city fell before Buford’s column could reach it, however. Afterwards, Buford received orders from Brig. Gen. Isaac Huger to fall back to Hillsborough, NC. In Charleston, British Lt. Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis, who would soon assume command of all British forces in the south, learned of the existence of these Patriot reinforcements. On May 27, he sent troops in pursuit. They were mounted troops of the British Legion, mostly loyalists under the command of the infamous Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton. Throughout the southern campaign, the 26-year-old Tarleton would establish for himself a reputation for cruelty and blood lust that was unsurpassed. Some of the acts attributed to him during this period were true and some were not, but his dubious reputation would become cemented in the minds of many Americans during this episode.

Tarleton set out in pursuit of Abraham Buford’s troops on May 27, leading around 300 of his Legion dragoons, some mounted infantry, and a detachment of the 17th Light Dragoons. Having a reputation for driving his forces unmercifully, Tarleton’s troops were able to quickly catch up, and closed in on Buford’s Virginians on May 29, on the border of North and South Carolina. It was farming country here, known as the Waxhaws.

When the two forces were still some miles apart, Tarleton issued a call for surrender, under a white flag of truce. In his message he wrote: “Resistance being vain, to prevent the effusion of human blood, I make offers which can never be repeated.” After conferring with his officers, Col. Buford made the decision to refuse Tarleton’s offer. He replied: “I reject your proposals, and shall defend myself to the last extremity.” The Patriot force then continued its march north towards Hillsborough, with Tarleton’s troopers continuing the pursuit.

By mid-afternoon of the 29th, Tarleton’s lead elements caught up with Buford’s column, attacking and destroying the small rear guard. Commanding that rear guard was Lieut. Thomas Pearson. Witnesses said that Pearson was sabered and knocked from his horse. While he lay on the ground, he continued to receive wounds; his face was mangled and there were cuts across his nose, lips, and tongue. Col. Buford halted his column, deploying his infantry in a single line across an open field, east of the Rocky River Road. He then issued a questionable order: his men were told to hold their fire until the dragoons were almost on top of them and then unleash a volley at point-blank range. When the charge came, the Virginians followed orders; they held their fire until the British were about 10 yards away. While their one volley did manage to empty a few enemy saddles, it wasn’t nearly enough and now the Virginians had no time to re-load their muskets. In a flash, Tarleton’s troopers were in among the Continentals, hacking men down with their sabers, wholesale.

Quickly realizing the battle was lost, Buford sent forward a white flag of surrender. About this time, Tarleton’s horse was killed, going down and momentarily trapping its rider. Some of his nearby troops became enraged, believing the Patriots were not honoring their own white flag. These troops are said to have continued sabering Patriot soldiers as they tried to surrender. Abraham Buford and some of his troops did manage to escape the field but his command was destroyed. Continental casualties totaled around 113 killed, 147 wounded, and 50 captured. Two Patriot 6-pounder artillery pieces and 26 baggage wagons were likewise captured. Compared to this, Tarleton’s losses were negligible. The battle would long be remembered as “Buford’s Massacre” and many of the Patriot dead lie today in a mass grave at the battlefield site.

Banastre Tarleton’s reputation for cruelty was established at the Waxhaws. Nicknames like “Bloody Ban” and “Bloody Tarleton” began to be used to describe him and the phrase “Tarleton’s Quarter” would become a Patriot battle cry.

Even though severely wounded in this action, Lieut. Thomas Pearson managed to survive his injuries, living until 1835. He was 84 when he died; his last years were hard on him. According to his pension application, he “received sundry wounds in his head and arms, which have rendered him, in his present advanced stage of life, incapable of maintaining himself by labour (sic).” On January 12, 1813, the Commonwealth of Virginia granted Pearson’s request for relief. He received an immediate payment of $50, with an annual pension payment of $60.

Today, this Revolutionary War veteran lies at rest in a quiet cemetery in Henry County, VA.