Emerging Revolutionary War is honored to share the post below by guest historian Kerry Mitchell

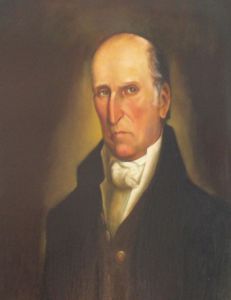

Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Richard Henry Lee, George Mason, Patrick Henry…when thinking about the period before and during the American Revolution these names come up as some of the great Virginians who were involved in the founding of our nation. While these men were great on their own accounts, there were other Virginian men who helped shaped our nation. Thomas Blackburn of Prince William County is one of these who history tends to glance over even though during the 1760s and 1770s, he was an important figure in American history.

Thomas was born in Prince William County around 1742 to Richard and Mary (nee Watts) Blackburn. Richard Blackburn was a native from Ripon, England who came over in the early 1700s and settled in Gloucester County, Virginia before moving to Prince William County in 1733. In addition to being a carpenter and farmer, Richard was involved in Prince William County politics and served as a Justice of the Peace. Not much is known about Thomas’s early childhood. He inherits his family home and farm, Rippon Lodge in 1760. That same year he marries Christian Scott with whom he has six children with. By 1762, Thomas receives a captain’s commission from the governor. With the French and Indian War ending it is unclear to what extent he served. We do know that in September 1766 he was serving as a Justice of the Peace for Prince William County. In 1772, Thomas was elected to be one of the Prince William representatives to the House of Burgesses.

Thomas’s election to the House coincided with the brewing unrest brewing between the colonists and Great Britain. After the Boston Tea Party and Britain’s passage of the intolerable Acts, Thomas was amongst the group of members who drafted the resolution that would call for a day of prayer and fasting for the people of Boston. Lord Dunmore believed the resolution was an insult to King George III and he dissolved the House on My 26th. Thomas was among the 22 ex-members who met at Raleigh Tavern and decided they would support a continental boycott of British goods. He went back to Prince William County to have the resolution passed by county leaders (which they did on June 6th). From 1774-1776, Thomas served in the first four Virginia conventions and involved himself in many committees dealing with the unrest. He was part of the committee offering George Washington the command of Virginia’s militia and as well as the committee with George Mason and Henry Lee II raising troops to defend Virginia. In the spring of 1776, Thomas lost his seat to attend the 5th Virginia Convention to Cuthbert Bullitt.

After losing his seat to Bullitt, Thomas was appointed as a Lt. Colonel of the 2nd Virginia State Regiment. After being passed over for a promotion, Thomas gave in his resignation on June 10, 1777. While he was out of the army officially, Thomas did not stay out of the fight for long. He rejoined the Virginia Militia as a volunteer. He fought at the battle of Germantown, Pennsylvania in October 1777. During this battle, he was wounded in the leg which ended his military career. He returned to Rippon Lodge in Woodbridge, Virginia to continue farming and entertaining his many friends. This included George Washington whom Thomas became related to through marriage when his daughter, Julia Ann, married George’s nephew, Bushrod Washington. On July 7, 1807, Thomas passed away at Rippon Lodge where he is buried in the family cemetery.

*Originally from New York, Kerry Mitchell is currently the Historic Interpreter at Rippon Lodge Historic Site, part of Prince William County’s Historic Preservation Division. She has a B.A. in Historic Preservation from the University of Mary Washington, a M.A. in American History from George Mason University and a graduate certificate in Museum Collection Care and Management from The George Washington University. She has previously worked at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, Reston Historic Trust, and the Fire Island National Seashore.*

Debuting yesterday, the Campaign 1776, an initiative by the Civil War Trust, released an animated map that covers the “entirety of the American Revolution,” according to Civil War Trust Communications Manager Meg Martin.

Debuting yesterday, the Campaign 1776, an initiative by the Civil War Trust, released an animated map that covers the “entirety of the American Revolution,” according to Civil War Trust Communications Manager Meg Martin.