In March 1776, a quiet hill overlooking Boston Harbor became one of the first turning points of the American Revolutionary War. Dorchester Heights, rising above the southern approaches to Boston in what is now South Boston, played a decisive role in forcing the British Army to evacuate the city. The dramatic occupation and fortification of the Heights by American forces under General George Washington transformed a long, grinding siege into a strategic victory that reshaped the war’s momentum.

After the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775 and the bloody clash at Bunker Hill in June, British forces under General Thomas Gage and then William Howe found themselves effectively trapped in Boston. Surrounding militia units from Massachusetts and neighboring colonies formed a loose ring around the city, beginning what became known as the Siege of Boston. When George Washington arrived in July 1775 to take command of the newly formed Continental Army, he inherited a force that was determined but poorly supplied and short on artillery.

Throughout the fall and winter of 1775–1776, Washington searched for a way to break the stalemate. A direct assault on Boston would have been costly and risky. Instead, he looked to geography. Dorchester Heights, commanding sweeping views of the harbor and the city, offered a strategic advantage. If American forces could fortify the Heights with cannon, they would threaten both the British fleet and the troops stationed in Boston. Control of this high ground would make the British position untenable. The British Navy had encouraged British General Howe (now commanding the British forces in Boston) to take the position due to the Navy’s vulnerability if the Americans were able to command the heights with artillery. Howe underestimated the importance of the heights and also believed the Americans lacked the proper artillery and strength to hold it.

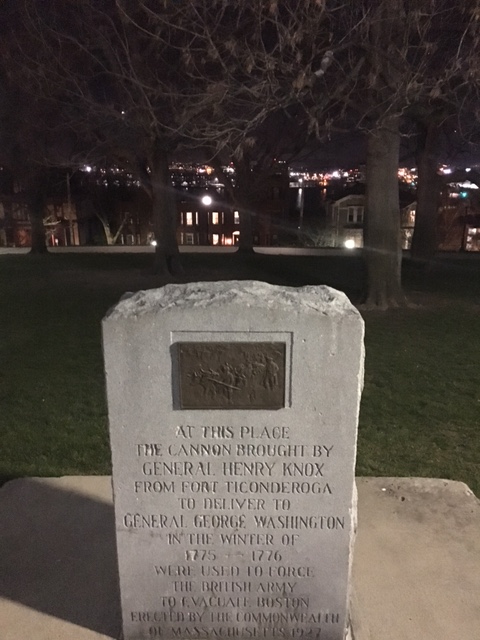

The key to Washington’s plan lay in artillery. In late 1775, Colonel Henry Knox undertook an audacious mission to transport heavy cannons captured from the British at Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York. Over the winter, Knox and his men hauled approximately 60 tons of artillery—an operation later dubbed the “Noble Train of Artillery”—over 300 miles of frozen rivers and snow-covered terrain to Cambridge, Massachusetts.

These cannons provided Washington with the firepower necessary to implement his strategy. By early March 1776, conditions were ripe. The ground was still frozen, making it easier to move heavy equipment and but would challenge their skills at building fortifications.

On the night of March 4, American troops moved silently toward Dorchester Heights. Under the cover of darkness and diversionary bombardments from other positions, they began constructing fortifications with remarkable speed. Using pre-prepared materials—fascines (bundles of sticks), chandeliers (wooden frames filled with earth), and hay bales—they built defensive works capable of withstanding British cannon fire.

By dawn on March 5, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre, British sentries were stunned to see formidable American fortifications atop the Heights, bristling with cannon aimed at the city and harbor. General Howe reportedly exclaimed that the rebels had accomplished more in one night than his army could have done in months. The strategic implications were clear. From Dorchester Heights, American artillery could rain fire down on British ships and troop positions. The Royal Navy, essential to British supply and mobility, was now vulnerable. Remaining in Boston was a risk that Admiral Molyneux Shuldham was not willing to take and pushed Howe to respond quickly.

General Howe initially planned a counterattack to dislodge the Americans. However, a fierce storm on March 6 disrupted preparations and made an amphibious assault difficult. Also, Washington got word of the planned British assault and increased his manpower on Dorchester Heights to nearly 6,000. The memory of heavy British casualties at Bunker Hill also weighed heavily. Dorchester Heights were even stronger and more defensible than Breed’s Hill had been the previous year.

Facing the prospect of severe losses and an increasingly precarious situation, Howe reconsidered. Negotiations—informal and indirect—suggested that if the British evacuated Boston without destroying the town, American forces would not attack during the withdrawal.

On March 17, 1776, British troops and Loyalists began evacuating the city. More than 11,000 soldiers and nearly 1,000 Loyalists boarded ships and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia. The Siege of Boston was over, and the city was firmly in American hands for the remainder of the war.

The occupation of Dorchester Heights marked the first major strategic victory for the Continental Army under Washington’s leadership. It demonstrated the effectiveness of coordinated planning, logistical ingenuity, and the intelligent use of terrain. Rather than launching a costly frontal assault, Washington had leveraged geography and artillery to compel the enemy’s withdrawal.

This victory also boosted American morale at a critical time. The war was far from won—indeed, it would intensify dramatically later in 1776 with British campaigns in New York—but the successful eviction of British forces from Boston showed that the Continental Army could achieve meaningful results.

Moreover, Dorchester Heights solidified Washington’s reputation as a capable commander. His cautious but decisive approach, combined with Knox’s logistical triumph, set a pattern for future operations. The event underscored the importance of high ground in military strategy, a lesson that had already been evident at Bunker Hill but was applied with even greater effect in March 1776.