After his first battlefield victory at the Battle of Harlem Heights on September 16, 1776, General George Washington wrote “The General most heartily thanks the troop commanded yesterday by Major Andrew Leitch, who first advanced upon the enemy, and the others who resolutely supported them.” The battle was a small victory for the American army, but instilled some confidence in the men who had suffered many defeats since August on Long Island and lost New York City to the British. One of the main players in this action was Major Andrew Leitch. A little known Continental officer who at the time was considered a rising star, but today is mostly forgotten.

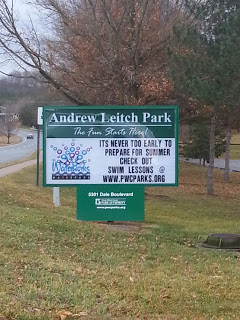

But my connection with Andrew Leitch goes beyond my love and interest of the American Revolution, it is more personal than that. In 2008 I met the woman that became my wife. At the time, she ran a park locally named Andrew Leitch Park. Having worked here locally for a few years, I was not aware of who the park was named after. I did a quick search of the name Andrew Leitch and realized we had a Revolutionary War hero. In my ignorance thinking everyone was as interested in history as I was, I assumed my future wife knew this fact. Of course…she didn’t. But now I had an “in” to keep talking to this young lady. And of course…she saw through it and had little interest in Andrew Leitch but it worked out and now we are married and have two great young kids. So, I partly owe all of this to Mr. Andrew Leitch.

But my connection with Andrew Leitch goes beyond my love and interest of the American Revolution, it is more personal than that. In 2008 I met the woman that became my wife. At the time, she ran a park locally named Andrew Leitch Park. Having worked here locally for a few years, I was not aware of who the park was named after. I did a quick search of the name Andrew Leitch and realized we had a Revolutionary War hero. In my ignorance thinking everyone was as interested in history as I was, I assumed my future wife knew this fact. Of course…she didn’t. But now I had an “in” to keep talking to this young lady. And of course…she saw through it and had little interest in Andrew Leitch but it worked out and now we are married and have two great young kids. So, I partly owe all of this to Mr. Andrew Leitch.

Who was this little known hero and why did have a park named after him in Prince William County, VA? In 1774 Andrew Leitch moved to Virginia from Maryland and began a new life in Northumberland County. He and his wife Margaret had three children and Leitch must have had influence because he was able to secure a commission as Captain in the 3rd Virginia Regiment on February 6, 1776. In this capacity he recruited men from Prince William County and led the Prince William Battalion (which also included men from Loudoun County). The Prince William Battalion joined the rest of the 3rd Virginia in Williamsburg in late February. Soon though Leitch received a promotion on June of the same year to Major in the 1st Virginia Regiment (though there is one source that places his promotion to Major on March 18th). As Washington moved his Continental Army from Boston to New York City in March 1776, he called for reinforcements. Men of the 1st Virginia and 3rd Virginia were called to join Washington in New York. For reasons unknown, the 1st Virginia was slow to get to New York. Leitch seemed to be a man of action as he joined his former men in the 3rd Virginia on their march to New York as they were a few weeks ahead of the 1st Virginia.

The 3rd Virginia did not arrive in New York in time for the disastrous Battle of Long

Island, arriving in early September to join the American army on Harlem Heights. Washington was happy to see his fellow Virginians and he needed the reinforcements. The Americans had lost New York City and were pushed off of Long Island, all the way up to the northern tip of Manhattan Island. The Americans needed something to encourage them, a battlefield victory. Major Andrew Leitch played a crucial role in delivering that victory, though at a horrible cost.

Part 2 will cover Andrew Leitch’s role in the Battle of Harlem Heights and his once forgotten legacy.