For part one, click here.

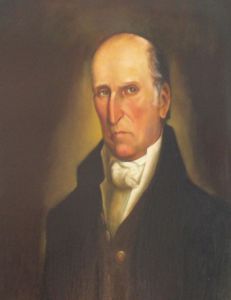

Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan, the “Old Wagoner,” as he was known, commanded a light infantry corps assigned to Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s southern army. Morgan met with Greene in Charlotte, North Carolina on December 3, 1780. Implementing a Fabian strategy, Greene split his army to harass the British while buying time to recruit additional soldiers. Greene ordered Morgan to use his 600-man command to forage and harass the enemy in the back country of South Carolina while avoiding battle with Lt. Gen. Charles Lord Cornwallis’ British army.

Once Cornwallis realized what was going on he dispatched Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion to track down Morgan’s command and bring it to battle. Tarleton commanded a combined force of Loyalist American troops. The Legion consisted of fast-marching light infantry and dragoon units. At its peak strength, the Legion numbered approximately 200 infantry and 250 dragoons. It was known for its rapid movements and for its ruthless policy of giving the enemy no quarter. Patriot forces feared Tarleton and his Legion, and for good reason.

By January 12, Tarleton’s scouts had located Morgan’s army in the South Carolina back country, and Tarleton began an aggressive pursuit. Morgan hastily retreated to a position at the Cowpens, a prominent crossroads and pasturing grounds for cattle. The field was about 500 yards long and about as wide, dotted with trees, but devoid of undergrowth, which served as a food source for grazing battle.

Once Morgan learned that Tarleton was pursuing him, he spread the word for local militia units to rendezvous with him at the Cowpens. Through the night, South Carolina militiamen drifted into camp. Morgan visited their camps, encouraging them to stand and fight. Morgan’s words were particularly effective; the grizzled veteran knew how to motivate these men. They would need to be prepared, because they faced a stern task the next day.

January 17, 1781 dawned clear and very cold. After his scouts reported Tarleton’s approach, Morgan rode among his men, crying out, “Boys, get up! Benny’s coming!” Morgan designed a defense in depth that was intended to draw the British Legion in and then defeat them by pouncing on their exposed flanks. He knew that his militia had a reputation of being unreliable, and his ability to maneuver was limited, so he elected to design and implement a defense in depth that took advantage of the terrain features of the Cowpens.

Tarleton was overconfident. He believed that Morgan’s command was hemmed in by the nearby Broad River and also believed that the cleared fields of the Cowpens were ideal ground for his dragoons, and concluded that Morgan must be desperate to fight in such a place.

Morgan had prepared three defensive positions. Selected sharpshooters out front and hiding behind trees manned the first line. They picked off a number of Tarleton’s dragoons as they advance, specifically targeting officers. Traditional accounts indicate that they downed 15 of Tarleton’s dragoons this way. Confused, the dragoons retreated.

Having accomplished their initial goal, the sharpshooters then fell back about 150 yards or so to join the second line, which consisted of Brig. Gen. Andrew Pickens’ militiamen. Morgan asked these men to stand long enough to fire two volleys, after which they were to fall back to the third—and main line—manned by Col. John Eager Howard’s Continentals, another 150 yards or so in the rear of the second line. Thus, Morgan had designed a textbook example of a defense in depth.

Some of the militia got off two volleys and then most of the militia fell back to a spot behind the third line. Tarleton orders his dragoons to pursue the retreating militiamen, and as the dragoons bore down on them with their sabres drawn, Col. William Washington’s Continental cavalry suddenly thundered onto the field, seemingly from nowhere. They routed the surprised Loyalist dragoons, who fled the field with heavy losses.

The infantry then engaged. With their drums beating and their fifes shrilling, the British infantry advanced at a trot. Recognizing that the moment of crisis had arrived, Morgan cheered his men on, rode to the front and rallied the militia, crying out, “form, form, my brave fellows! Old Morgan was never beaten!”

Tarleton’s 71st Highlanders, a veteran unit made of Scotsmen, which had been held in reserved, now charged the Continental line, their skirling bagpipes adding to the cacophony of battle. Howard ordered his right flank to face slight right to counter a charge from that direction, but in the noise and chaos, was misunderstood as a call to retreat. As other companies along the line began to pull out, Morgan rode up to ask Howard if he had been beaten. Howard pointed at the orderly ranks of his retreat and assured Morgan that they had not been beaten. Morgan then put spurs to his horse and ordered the retreating units to face about and, on his order, to fire in unison. Their deadly volley dropped numerous British soldiers, who, sensing victory, had broken ranks in a determined charge. The combination of this volley and a determined bayonet charge by the Continentals turned the tide of battle in favor of the Americans.

At the moment, the rallied and re-formed militia and Washington’s cavalry attacked, leading to a double envelopment of the British, who began surrendering in masses. Tarleton and some his men fought on, but others refused to obey orders and fled the field in a panic. Finally, Tarleton realized that he had been badly beaten and fled down the Green River Toad with a handful of his men. Racing ahead of his cavalry, William Washington dashed forward and engaged Tarleton and two of his officers in hand-to-hand combat. Only a well-timed pistol shot by his young bugler saved Washington from the upraised saber of one of the British officers. Tarleton and his remaining forces escaped and galloped off to Cornwallis’ camp to report the bad news.

And bad news it was: Tarleton’s Legion lost 110 dead, over 200 wounded and 500 captured. By contrast, Morgan lost only 12 killed and 60 wounded. His perfectly designed and perfectly implemented defense had worked even beyond the Old Wagoner’s wildest dreams and highest hopes.

Knowing that Cornwallis would pursue him, Morgan buried the dead and then withdrew to the north to live and fight another day. Morgan reunited with Greene’s army and the combined force headed for North Carolina. Morgan, whose health was fragile, soon retired from further duty in the field, but he had left his mark. Cowpens was his finest moment, and set a precedent for Greene to follow two months later at Guilford Courthouse.

(Courtesy of Campaign 1776/CWT)

*Suggestions for additional reading: for a superb book-length microtactical treatment of the Battle of Cowpens, see Lawrence E. Babits, A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998). This book is the primary resource consulted in drafting this article.

Debuting yesterday, the Campaign 1776, an initiative by the Civil War Trust, released an animated map that covers the “entirety of the American Revolution,” according to Civil War Trust Communications Manager Meg Martin.

Debuting yesterday, the Campaign 1776, an initiative by the Civil War Trust, released an animated map that covers the “entirety of the American Revolution,” according to Civil War Trust Communications Manager Meg Martin.

Russellborough doesn’t look like much now, but once upon a time, these ruins were one of the nicest homes along the North Carolina coast. Now, its spaciousness comes from the cavernous pavilion that protects the houses’ remains.

Russellborough doesn’t look like much now, but once upon a time, these ruins were one of the nicest homes along the North Carolina coast. Now, its spaciousness comes from the cavernous pavilion that protects the houses’ remains.

![030_30[1]](https://emergingrevolutionarywar.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/030_301.jpg?w=640)