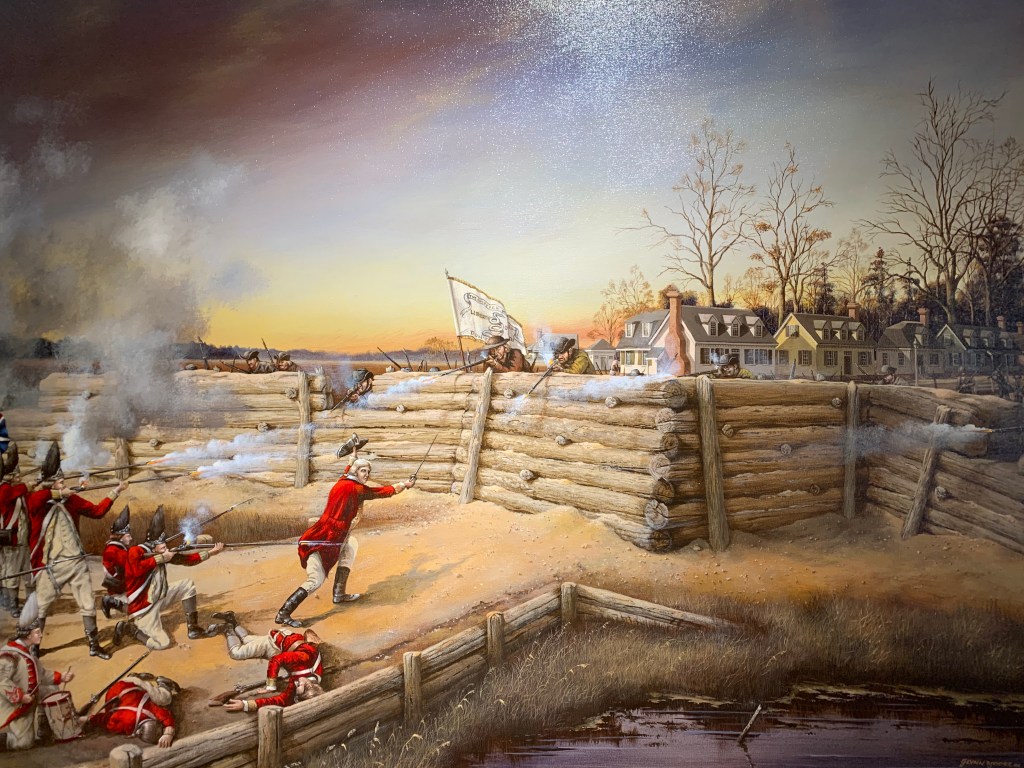

On the cold morning of December 9, 1775, a British force of redcoats marched out of their wooden stockade and advanced towards the rebel earthworks on the southern end of the Great Bridge. For days both sides were expecting an action, and now it was about to happen. Royal Governor Dunmore, believing that Patriot cannon from North Carolina were on their way to drive the British from Great Bridge, sent Captain Samuel Leslie with 120 men of the 14th Regiment of Foot to drive the Patriots out with a straight frontal assault.

Leading the attack were about 60 grenadiers of the 14th Regiment of Foot under the command of Captain Charles Fordyce. Behind them were some other British regulars, some Loyalist militia and some of Royal Governor Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment. Across the Great Bridge was a long causeway with swamp on either side. Any attack by the British would be across this this causeway with no other way to maneuver. At the southern end of the causeway were Patriot earthworks manned by Col. William Woodford’s 2nd Virginia Regiment. To their left were positioned some riflemen of the Culpeper Minute Men. Out on the causeway were some Patriot pickets, including the free African American Billy Flora.

As the British advanced across the bridge, they began to engage the American pickets. The pickets after firing for a few minutes began to pull back into the main American lines. Fordyce and the grenadiers continued to push forward despite receiving fire from the pickets as well as the extremely accurate Culpeper riflemen.

With the American fire alerting everyone, American reinforcements advanced into the main American lines. Lieutenant Edward Travis of the 2nd Virginia had his men hold their fire until the British advanced to point blank range.

The British grenadiers, marching forward six men abreast, hoped to rush the American position at the point of the bayonet. When they were just 50 yards from the American line, the 2nd Virginians aimed at the British soldiers and poured a heavy fire into them. Now the grenadiers were being hit from the flank by the American riflemen as well as from the front by the muskets of the 2nd Virginia. The fire was galling. Fordyce removed his hat and waved it enjoining his men to follow him into the American works. Fifteen paces from the American lines, Fordyce fell at the head of the column with 14 musket balls in his body.

Colonel Woodford remembered that “perhaps a hotter fire never happened or a greater carnage.” The British continued to engage for a little, but as more Patriot troops filled the American earthworks, and as the British sustained heavy fire the from the front and the right, they decided to pull back across the Great Bridge. They left behind a grisly scene, as the British suffered 17 men killed and 44 wounded or captured, about 50% of the attacking force. The Americans only had one man wounded in the hand.

The day had been an important Patriot victory. Dunmore was forced to cede the ground. William Woodford wrote to Patrick Henry that “the victory was complete . . . This was a second Bunker’s Hill affair, in miniature, with this difference, that we kept our post and had only one man wounded in the hand.”

To learn more about this significant, though often overlooked battle of the Revolutionary War, be sure to visit our Facebook page today, as historians from Emerging Revolutionary War will be filming videos in real time from the battlefield. Also, check out our Rev War Revelry with historian Patrick Hannum where we discuss in more depth the battle.