Baron Ludwig von Closen, aide–de–camp to French General Rochambeau, wrote in July 1781:

“I had a chance to see the American Army, man for man. It is really painful to see those brave men, almost naked with only some trousers and little linen jackets, most of them without stockings, but, would you believe it, very cheerful and healthy in appearance … It is incredible that soldiers composed of men of every age, even children of fifteen, of whites and blacks, unpaid and rather poorly fed, can march so fast and withstand fire so steadfastly’.”

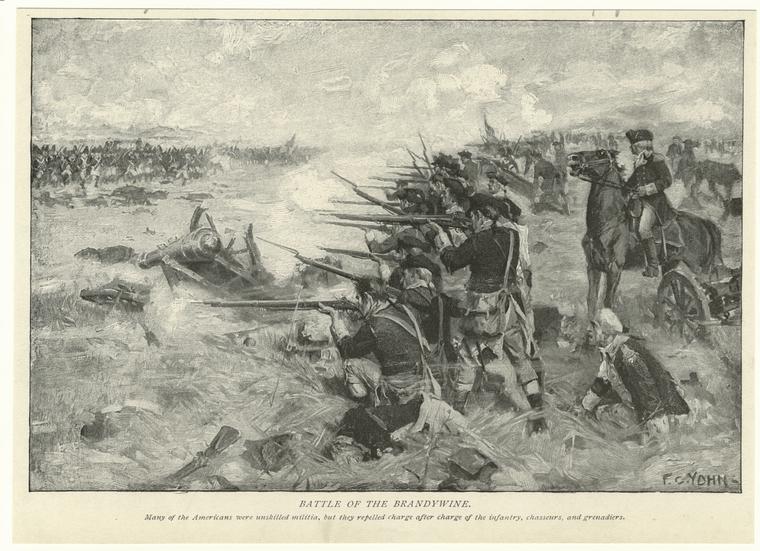

During the American Revolution, African-Americans, both freed and enslaved, fought for the patriots. Some wielded muskets in militia outfits whereas others were part of the Continental army. African-Americans were there from the Siege of Boston through the end of the conflict. In fact, until the Korean War the American Revolution was the last time a United States military force was integrated in time of war.

Although publications have been printed about the 1st Rhode Island or comparative studies between Africans that served for the British or patriots. However, the field needed a dedicated study of African-Americans that served in the Continental army. Enter John U. Rees.

A lifelong Bucks County, Pennsylvanian who has studied and written about the soldiery of the American Revolution for the past three decades. He is published many times over and this Sunday, he will join Emerging Revolutionary War at 7 p.m. on “Rev War Revelry.”

The discussion will include his new book, “They Were Good Soldiers’: African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783.” Which is now available for purchase online. ‘They Were Good Soldiers’: African Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783 begins by discussing the inclusion and treatment of black Americans by the various Crown forces (particularly British and Loyalist commanders, and military units). The narrative then moves into an overview of black soldiers in the Continental Army, before examining their service state by state. Each state chapter looks first at the Continental regiments in that state’s contingent throughout the war, and then adds interesting black soldiers’ pension narratives or portions thereof. The premise is to introduce the reader to the men’s wartime duties and experiences. The book’s concluding chapters examine veterans’ post-war fortunes in a changing society and the effect of increasing racial bias in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Besides the book dialogue, a general conversation about the roles of African-Americans in the American Revolutionary period. So, find your favorite brew, bring your questions and insights, and join John Rees and ERW on Sunday evening on our Facebook page.

For more articles by our guest historian John Rees, visit https://tinyurl.com/Rees-author-only . An online compendium of articles on African Americans in the Revolutionary era is available at https://tinyurl.com/Afr-Amer-Rev-War .