Valley Forge consists of acres of undulating countryside where General George Washington and some 11,000 Continental Army troops spent the winter of 1777-1778. Today, it is one of the nation’s most hallowed shrines. Few, if any, modern visitors recognize the woman who fought to save it, nor her heroic work as a nurse during the American Civil War.

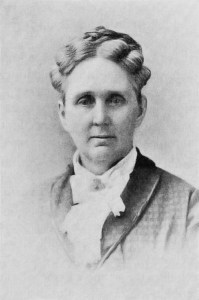

Read more: Civil War Nurse Saves Mount Vernon & Valley ForgeAnna Morris Ellis was born in Muncy, Pennsylvania, on April 9, 1824. On September 26, 1848, she married William Hayman Holstein. At 38 years old, Anna became involved in the Union army’s war effort during the American Civil War after the battle of Antietam in September 1862. Her husband returning home after serving a 90-day enlistment, told of wounded men lying in barns and fields around Sharpsburg, Maryland because there weren’t enough medical corpsmen. Despite an overhaul to the Union Army of the Potomac’s Medical Department by Dr. Jonathan Letterman earlier that summer, the combined evacuation of the Virginia Peninsula from their failed late spring and summer campaigns and the Second Manassas campaign outside of Washington, D.C. in August had left this medical department in a state of chaos, confusion, and wholly unprepared to meet the medical needs of such another large scale engagement as Antietam. Anna and her husband William immediately left for the Antietam battlefield in response to the distressing scenes he had painted for her.

The Holstein’s served for months around the Antietam battlefield, caring for the sick and wounded. Their role as post-battle caretakers continued just a month after the battle of Gettysburg when the large army field hospital of Camp Letterman opened just east of the borough on the York Road. This time, however, Anna was already numbed to the scenes of shattered limbs and the despondently ill wearied from disease. By this time her husband had secured a position with the U.S. Sanitary Commission which also setup at Gettysburg to aid the wounded and sick in the wake of the battle. That agency, along with the U.S. Christian Commission, offered supplies and personages to aid in the aftermath of not only Gettysburg, but other battles in the final years of the war.

Anna’s role for caring for those soldiers left behind by both armies was significant. She was made matron-in-chief of Camp Letterman by Dr. Cyrus Nathaniel Chamberlain, which, under her and Chamberlain’s care, attended to over 3,000 wounded soldiers. Anna continued to work at Camp Letterman until it closed on November 19, 1863. Later that day, both her and her husband sat on the platform near Abraham Lincoln while he delivered the Gettysburg Address. Following her work at Gettysburg, Anna continued to nurse the sick and wounded back to health. By the end of the Civil War in 1865 and into 1866, she worked as a matron in a hospital in Annapolis, Maryland, caring for returned prisoners of war that were sick or wounded.

In the post Civil War years, Anna turned to the preservation of the places and material culture from America’s first war for independence. She was no stranger to the importance of this era and the necessity of keeping the memory of those that served during that turbulent era alive for future generations. Anna’s great-grandfather was Capt. Samuel Morris. Morris was the captain of the First City Troop of Philadelphia when it served as George Washington’s body guard. Captain Morris was with Washington during the Ten Crucial Days and was on the field him at the battles of Trenton and Princeton. Morris even earned the sobriquet as leader of the “fighting Quakers.” Anna’s grandfather, Richard Wells, also served the American cause. He was commissioned to provision the U.S. fleet on the Delaware River during the revolutionary war.

One of her first missions was to save and restore George Washington’s Virginia estate, Mount Vernon. The home had fallen into significant disrepair, with the recent war years only aiding to its material decay. Both Anna and her husband, who also had strong ancestral ties to the War for Independence, were among the first to promote the struggles at Mount Vernon, the necessity for saving it, and the fundraising to back those plans. It was her skills in fundraising so successfully for Mount Vernon that led her to be named as regent for the Valley Forge Centennial and Memorial Association. Anna also was one of the founders, and also named regent as well, of the Valley Forge Chapter of the D.A.R.

By 1878, The Centennial and Memorial Association of Valley Forge, was incorporated in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Once incorporated, she led the charge as regent to save, acquire, restore and preserve General Washington’s Valley Forge Headquarters and surrounding acreage as parcels became available. Much needed funds for this charge would be needed, however. On June 19, 1878, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Continental Army marching out of Valley Forge, the Association held a large, organized event. With the funds generated from the anniversary commemoration, the Association was able to not only purchase General Washington’s Headquarters, but also additional acreage around the farm complex. They were also able to purchase original artifacts to place in the home, begin renovations to restore the home back to its 1777-78 appearance, and plant a tree from Washington’s Mt. Vernon on the property.

By 1893, when the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania assumed control of the camp sites and headquarters at Valley Forge, with Anna credited as the person “to whom the Nation is indebted more than any other” for her tireless efforts to ensure this national shrine was preserved and protected in perpetuity. Decades later, the National Park Service would assume ownership and operational leadership of the park from the state of Pennsylvania.

Anna and William’s home still stands in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania today at 211 Henderson Road. In 2021 the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission placed a marker at the entrance drive to the home. Anna’s work at saving material culture from the Revolutionary War and ensuring the legacy of the veterans of that conflict lived on was vast. Hopefully this small summation of her activities inspires others to dig deeper into her efforts.