Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian Kenneth Bancroft

“Nothing but War is talked of…This cannot be redressing grievances, it is open rebellion…”1

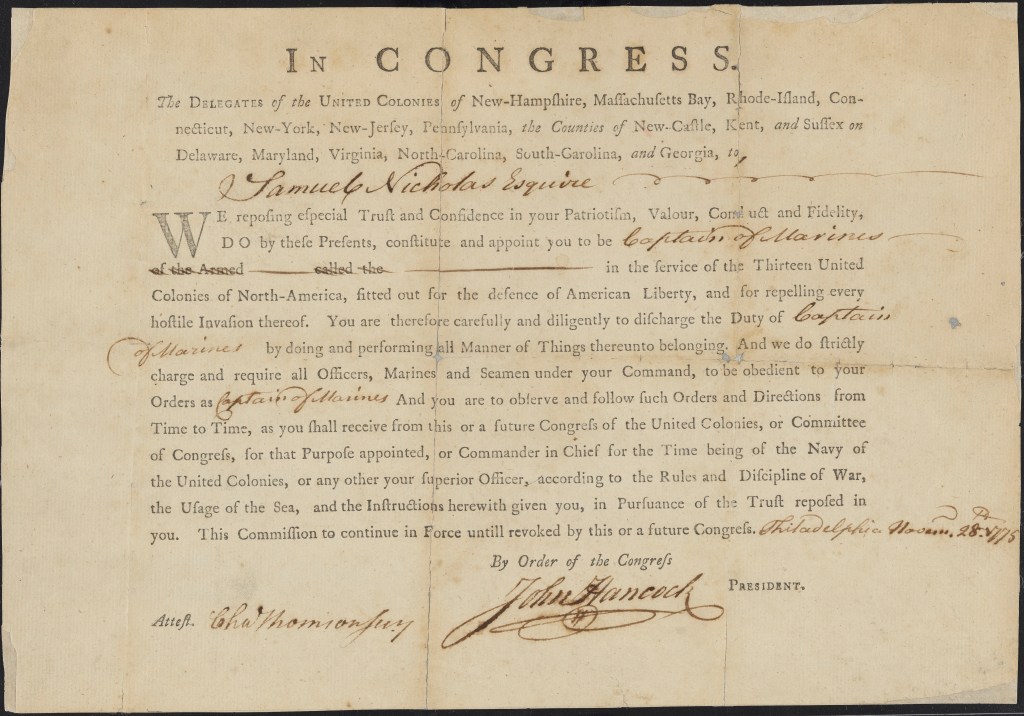

250 years ago on October 20, 1775 a 25 year old Englishman wrote these words in Alexandria, Virginia, noting that “everything is in confusion…soon they will declare Independence.”2.Nicholas Cresswell had arrived in America a year and a half prior to that entry in a journal that he kept to chronicle his venture to “shape his course in the world” and set up a new life inVirginia, “as I like the situation of that Colony the best.”3 He was aware of grumblings from colonials, but his focus was on land and his adventure had him traveling and trading with the Native Americans in the Ohio country and experiencing the slave culture in the colonies, especially the horrific sugar plantations in Barbados.

But what his journal is most known for is his observations and critique of the revolutionary world from Virginia to New York in 1774 through 1777. Cresswell’s misfortune, among others, was that he arrived in America seeking opportunity just as the Imperial Crisis over the Intolerable Acts had began. News of, and reaction to the closure of the port of Boston frequently disrupted his schemes and social life. As an Englishman still loyal to the Crown, his Revolutionary War journal offers a unique outsider look at the costs of the conflict in the country and towns as opposed to the more common tomes of soldier life.

“No prospect of getting home this winter, as I am suspected of being a Spy.”4 Cresswell’s tenure in America was tenuous. Unsuccessful in trying to establish himself with land and basically broke, he blamed his misfortune on the “Liberty Mad”5 political climate that considered him a ‘Tory’ who would not commit to the cause. His penchant for getting into drunken political arguments did not help and kept getting him in trouble with local Committees of Safety.

“Am determined to make my escape the first opportunity.”6 By that point Cresswell knew it was time to forgo his quest and return to England, but the question was how, especially with non- importation measures and the war closing ports. What followed next for Cresswell was an amazing account of encounters with revolutionary notables and locations such as Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and British General Howe in Philadelphia, Williamsburg, and New York respectively. Ultimately, Cresswell was able to secure passage back to England where he reluctantly picked up where he left off by order of his father to “shear or bind corn.”7

1 Nicholas Cresswell, The Journals of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777, (North Charleston, South Carolina: reprinted 2024), 97.

2 Ibid, 97.

3 Ibid, 3.

4 Ibid, 101.

5 Ibid, 47.

6 Ibid, 143.

7 Ibid, 214.

The Journals of Nicholas Cresswell was first published in 1924 and offers a candid account of the American Revolution from a viewpoint not typically explored. Its accounts of mustering militia, salt shortages, political pulpits, and anti-Tory riots and fights add color to our revolutionary origins. Add to that Cresswell’s experiences with the Native Americans in the Ohio country and the plantations in Barbados which further inform our understanding of our colonial past. Join Cresswell’s journey! To read more about Cresswell’s journey click here. The blog is an online platform and resource to follow his daily posts as they occurred 250 years ago. Keyword search features and research links are featured as well. Follow along on Facebook, too, at Nicholas Cresswell Journals.