Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian Andrew J. Lucien. Brief bio of Andrew follows the post.

Bunker Hill, Valley Forge, Yorktown, July 4, George Washington. These are the most common images that come to mind when the American Revolution is mentioned by most people. The collective unconscious of America has become steeped in the imagery of glorious American victories to win our independence from the superpower of the time. However, what many are unaware of is the unusual campaign that took place from 1775 to 1776, in an attempt to gain the support of Canada in our quest for independence. This campaign featured several battles, with the key one being the Battle of Quebec. This marked a significant turning point in the campaign and the war as a whole.

In 1775, the fate of the impending schism between Britain and its North American colonies was all but sealed. The colonial fervor had reached a climax at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in the spring of 1775, setting the mother country and its colony down a path of armed conflict. As tensions rose in 1775, Ethan Allan, along with Benedict Arnold, captured the British fort at Ticonderoga in early May, resulting in much-needed guns for the colonials. With successful action undertaken in the northern reaches of New York state, the Continental Congress approved plans to invade Canada. Intelligence led the patriots to believe that there were fewer than 700 British soldiers stationed in the Canadian territory and that the popular sentiment in the territory was in favor of rebellion, and that they, too, might take up arms against the British Crown.

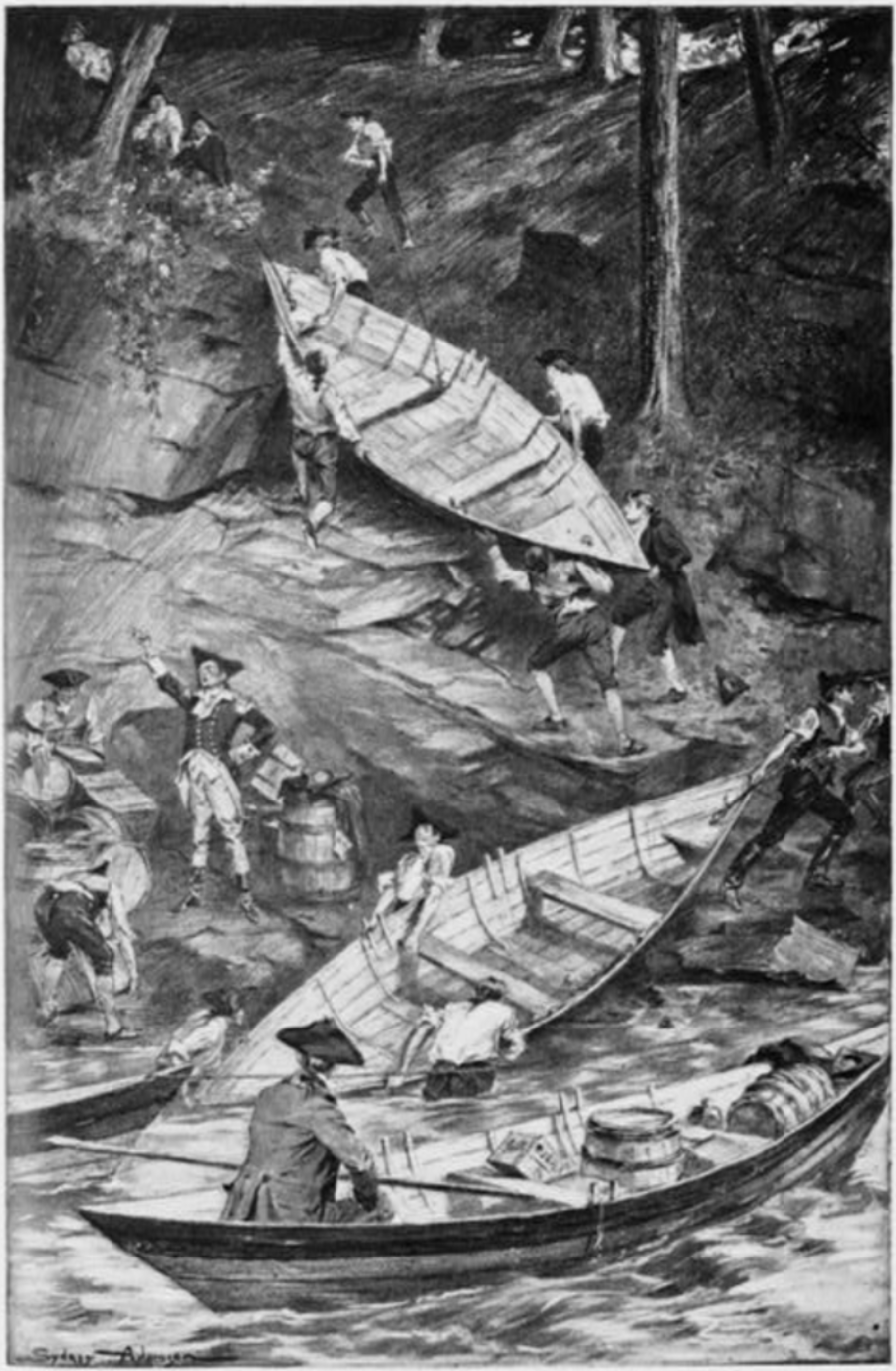

By late September, Ethan Allan unsuccessfully attempted to capture Montreal. Near the same time, Benedict Arnold began to lead a force of around 1,100 men from Boston on an enterprise aimed at aiding in the capture of Canada (only about 600 would reach their destination). These men would eventually join forces with Richard Montgomery’s force around Quebec in December of 1775, “to finish the Glorious work you begun,” to quote George Washington. By the time Arnold’s men reached Canada, they were “in a very weak condition.” Montgomery’s force was moving north from Lake Champlain. His men captured Fort Chambly and Fort St. Johns. Following these captures, the force under Montgomery advanced on Montreal. The British governor, Guy Carlton, took approximately 150 men with him from Montreal to Quebec, believing it to be a more important and defensible position. Montreal was easily captured on the 13th. Montgomery did not rest long after capturing the fort, leaving a small garrison in Montreal and heading to join forces with Arnold’s men at Point aux Trembles. Montgomery, “…was anxious, after the capture of Chamblee, St. Johns and Montreal, to add Quebec, as a prime trophy to the laurels already won.”

With the combined force of Montgomery and Arnold now outside of Quebec, Montgomery sent Carlton multiple messages to surrender, which were all rejected. Upon hearing the refutation of his final offer, Montgomery was supposed to have said he would “dine in Quebec or Hell at Christmas.” Finally, with all other options seemingly exhausted, it was planned to forcibly take the city by sending Arnold’s corps to assault the lower town via St. Roque. Montgomery was to attack the lower town via Pres-de-Ville, near Cape Diamond. There was to be a fient east of St. John’s Gate under Colonel Livingston and one at Cape Diamond under Major Brown. The ultimate goal was to meet in the lower town, then storm the upper town.

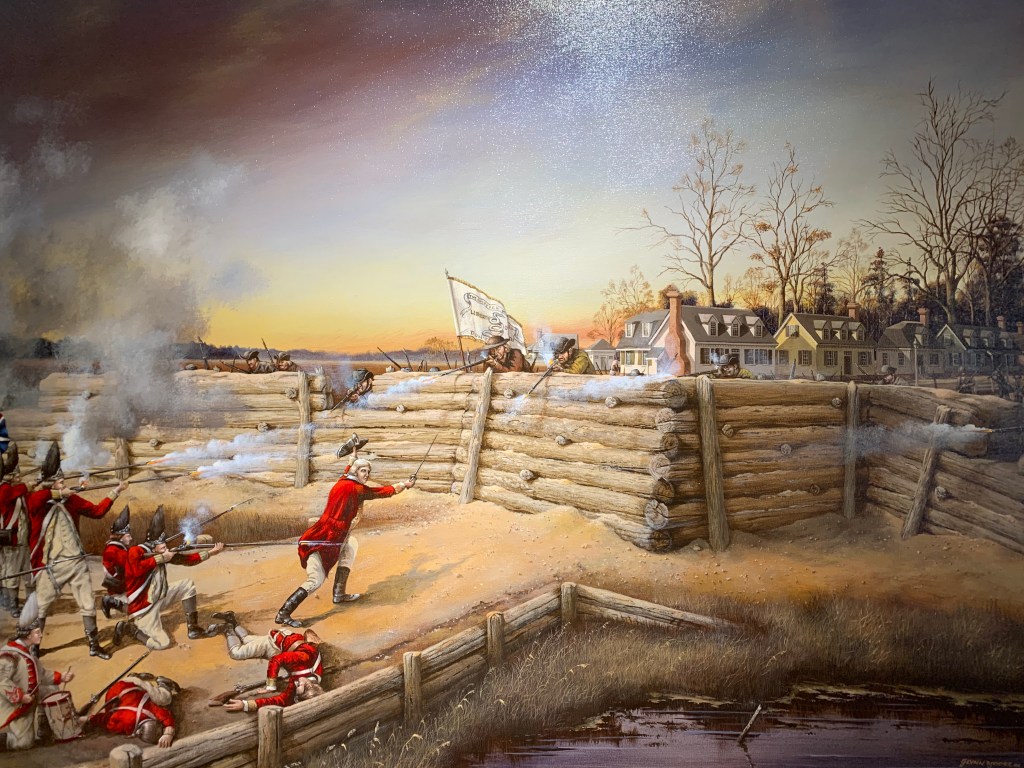

Around midnight as the 31st began, clouds began to fill the sky and snow began to fall. This was a signal to the Americans to begin preparing for an assault, using the snowstorm as cover. By 2 a.m., the American troops began their movements. At about 4 a.m., Captain Malcolm Fraser saw flashes and lights on the Heights of Abraham. Fraser suspected that the lights were a sign of the American troops’ movement and ordered his guards to arm. The British began to play their drums and ring their bells to alert the men of Quebec to prepare for the city’s defense. The Americans launched two rockets to signal the beginning of their assault. With the rockets illuminating the early morning sky, the rebels began to fire their muskets into the British line. With the darkness of the morning still upon the soldiers, the British were unable to see their opponents, except when their muskets would flash and illuminate their heads. They used the flash of the muskets to guide their return volleys. The Americans began to launch artillery into Quebec from St. Roque. When Arnold saw the rockets in the morning sky, he led about 600 men from St. Roque to attack the British works at Saut-au-Matelot. Montgomery led his force of about 300 men to attack the works at Pres-de-Ville. Montgomery believed that this location was ripe for an escalade.

Arnold and the rest of his column advanced along the waterfront through St. Roque. The British sailors stationed there rained fire down on the Americans from atop the ramparts. The Americans “could see nothing but the blaze from the muzzles of their muskets.” As the Americans pressed forward, they lost the cover of the houses. Arnold was hit in the leg by enemy fire near the first barricade, and he was taken from the field by two men. Arnold tried to rally his men as he was taken away. Despite the setback, the Americans under Daniel Morgan pressed forward and used their ladders to scale and capture the first barricade at Saut-au-Matelot, along with 30 British troops. Here, the Americans found their muskets useless due to the snow. Many colonial troops resorted to confiscating British muskets. The Americans continued about 250-300 yards further to attempt to capture the second barrier, where they met opposition from the British. The Americans, on a narrow street, moved against the British, who had their own strong defenses, including a 12-foot-high barrier, cannons, and two lines of soldiers ready to repulse the attacking Americans. The British fired down on the Americans from the tops of the buildings. The colonial troops attempted to climb the barrier but were forced back by the British inside with their bayonets fixed. They then fired from under the cover of the houses, allowing the British to see them only as they moved from house to house. The attackers contemplated retreating; however, they tarried, ultimately a dire mistake. Carleton, aware of the developing assault, men to attack the flank of the Americans. With the Americans now flanked and facing stiff opposition in front, they surrendered to the British force.

Montgomery and his men suffered a far more deadly fate. As his column approached Pres-de-Ville, Captain Barnsfair had his men next to their guns and at the ready when the Americans arrived. The British had erected a barrier here with a battery. The Americans advanced within 50 yards of the British guns and halted, then resumed their advance, likely because they believed the soldiers were not on guard. Barnsfair “declared he would not fire till he was sure of doing execution, and… waited till the enemy came within… about thirty yards’ distance” and then called out, “fire!” “Shrieks and groans followed the discharge.” The fire of canister, grapeshot, and musketfire was deadly. When the fire stopped, the field of battle was clear with no rebels left standing on the field. Montogemery was one of the casualties of the action, found lying on his back with his arm still in the air. Seeing the folly of another assault, the remaining men retreated. An officer of Carlton’s declared the battle “a glorious day for us, and as compleat a little victory as was ever gained.” When the dust settled, the Americans suffered about 50 killed, 34 wounded, and 431 captured or missing, while the British defenders lost only 5 killed and 14 wounded. The fighting had lasted only around 4 hours.

Bibliography:

“An Account of the Assault on Quebec, 1775,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 14, no. 1 (1890): 47–63.

Blockade of Quebec in 1775–1776 by the American Revolutionists (les Bastonnais). Historical event, Quebec City, 1775–1776.

Caldwell, Henry. The Invasion of Canada in 1775. Quebec: Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, [microform].

Hatch, Robert McConnell. Thrust for Canada: The American Attempt on Quebec in 1775–1776. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979.

Henry, John Joseph. Account of Arnold’s Campaign Against Quebec, and of the Hardships and Sufferings of That Band of Heroes Who Traversed the Wilderness of Maine from Cambridge to the St. Lawrence, in the Autumn of 1775. Albany: Joel Munsell, 1877.

Bio:

Andrew Lucien is a social studies curriculum director at the Cleveland Metropolitan School District, host of The Civil War Center podcast, and founder of thecivilwarcenter.com. He has written extensively on the Civil War and Revolutionary War.