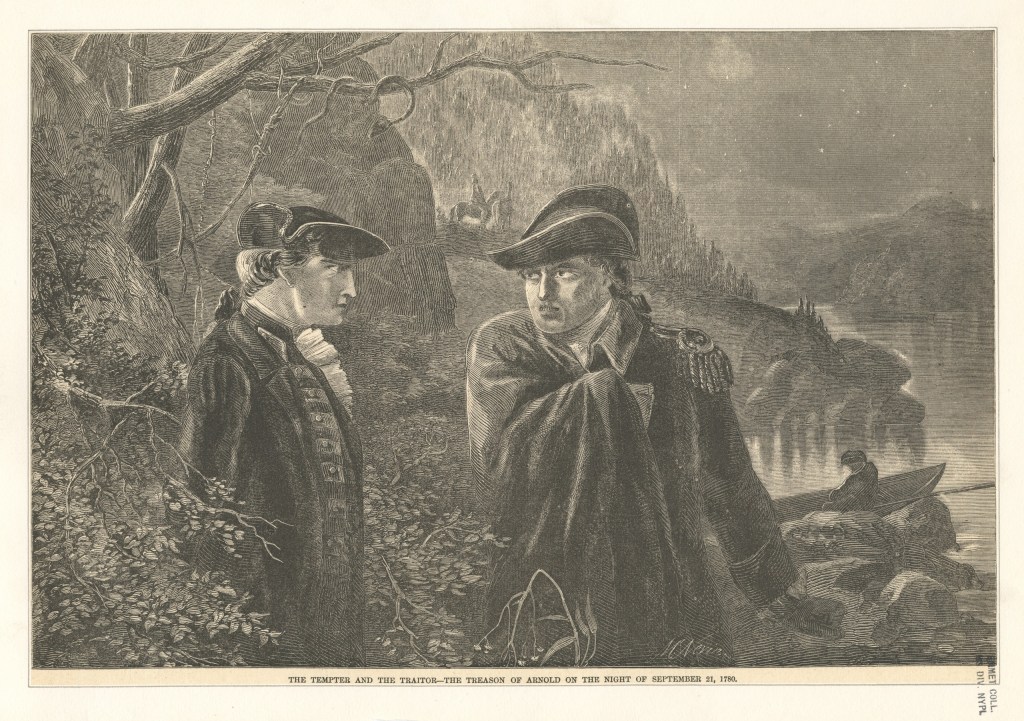

Major Andre cautiously rode his horse through unfamiliar territory between American and British lines. It was a neutral zone wreathing with unforgiving bands of Cowboys and Skinners, but ground that Andre, garbed in civilian clothing, needed to cross in order to return to New York City. He had experienced several close brushes with American posts, and his guide, Joshua Smith, rather than risking any run-ins with Tories, had decided to turn around when they were some twenty miles from British lines. Andre was on his own for the final leg of the journey. All seemed to be going well until he arrived just outside of Tarrytown and three men with leveled muskets emerged from the bushes astride the path.

The capture of Major Andre during the morning of September 23, 1780 was the moment that Benedict Arnold’s plot to surrender West Point to the British officially unraveled, saving the garrison, the Hudson River, and potentially the revolutionary cause for the Americans. It was a moment that was entirely avoidable had Smith agreed to carry Andre back to the Vulture downriver rather than insisting on taking the overland route and subsequently abandoning the officer to the mercy of whatever lay between the opposing lines. Unfortunately, for Andre, his fate would be determined by a group of “volunteer militiamen,” but most likely crooked highwaymen.

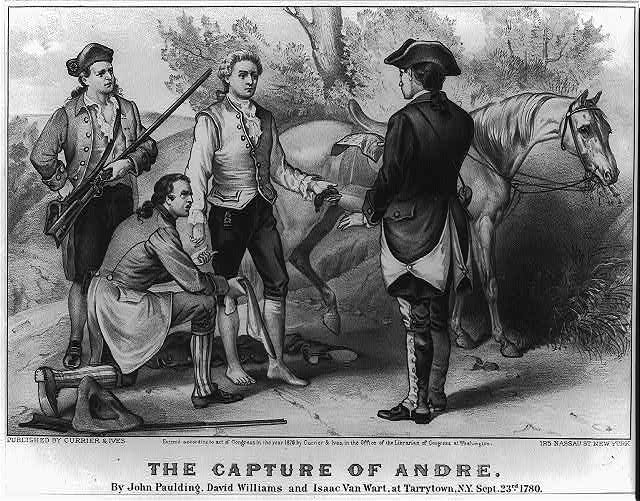

The meeting exchange that occurred between the British intelligence chief and the armed men blocking his path proved to be the most costly of the latter’s short life. Seeing that one of the militiamen was dressed in the green jacket of a Hessian jaeger, Andre incorrectly assumed that they belonged to his side, or the “lower party,” as he had asked them. The man, John Paulding, duped Andre, and answered in the affirmative. Relieved, the major revealed to them that he was in fact a British officer. Paulding then informed him that they were Americans, and after Andre handed him a pass written by Arnold, he threw it aside and began searching the rider, taking the valuables he carried with him. All this could have been ignored by Andre if they had then let him continue on to New York City, but the greedy militiamen then proceeded to remove the fine boots of a British officer he was wearing, and then his socks. What he was hiding underneath would be the evidence eventually needed to incriminate him and Arnold: documents relating to West Point and its defenses. The ragtag party of Americans had just nabbed themselves a spy.

Following his capture, Andre was taken to the Continental camp at North Castle and turned over to Lt. Col. John Jameson of the 3rd Continental Dragoons, who examined the dispatches. Seeing Arnold’s name on the papers, Jameson was not about to accuse an American hero of conspiring with the enemy. Instead, he sent Andre with an escort back to Arnold’s camp and scribbled off a message to the general: “I have sent Lieutenant Allen with a certain John Anderson [Andre’s moniker] taken going to New York. He had a pass signed with your name. He had a parcel of papers taken from under his stockings, which I think of a very dangerous tendency … The papers I have sent to General Washington.”[1] It was only a matter of time before Arnold realized that his plot was about to be discovered.

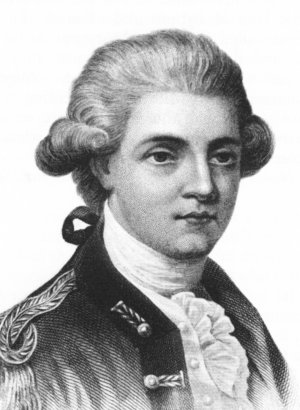

Andre, however, would never make it back to Arnold’s headquarters. Later that day, Maj. Benjamin Tallmadge, Washington’s chief intelligence officer and famed leader of the “Culper Ring,” arrived in Jameson’s camp and after learning of the man carrying suspicious documents, convinced the lieutenant colonel to return the suspect to camp.

Riding back to Arnold with Lt. Allen, Andre must have felt relieved that he had dodged another bullet. Much to his dismay, the next day he would be turned around and delivered to Maj. Tallmadge, where his fate as a spy would be decided.

[1] Quoted in Stephen Brumwell, Turncoat: Benedict Arnold and the Crisis of American Liberty (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 269.