Just over two weeks ago, ERW historians Billy Griffith, Phillip Greenwalt, Mark Maloy, Rob Orrison and Kevin Pawlak took a long weekend trip up to upstate New York. This was the fourth year that ERW authors have gotten together to take a “field trip” to see sites related to the French and Indian War and the American Revolution.

The trips not only serve as chances for research, but also to make new connections with public historians working in the American Revolution era. Along the way, we posted several videos from locations to give our followers an idea of some of the great places to visit out there. Again, our goal is to not just share this history, but to get people to visit these great sites.

Sites visited on the first day included the Stony Point Battlefield, where Americans under Gen. Anthony Wayne over ran a surprised British outpost. Reading about this action almost rings empty until you stand on the ground. Looking at the steep terrain that Wayne’s men climbed after traversing through a wetland, it is hard to imagine how the Continentals were able to take the British fort with so few casualties. Later that day we made a quick stop at George Washington’s headquarters in Newburgh. Here Washington lived from April 1782 to August 1783 and where he learned of the cease fire with the British, wrote his now famous circular letter to the colonial governors on his vision for the new government. Most importantly, here Washington responded to the Newburgh Conspiracy of his officers looking to possibly over throw the civil government. This site is also important in the history of the museum field as it is the first publicly owned historic site in the United States, opened in 1850 as a museum. A worthwhile nearby site, the New Windsor Cantonment site, preserves the camp site of the Continental Army during the 1782-1783 time period. Several of the buildings are rebuilt, including the Temple of Virtue, where Washington made his impassioned speech to his officers (with the assistance of his glasses) to diffuse their discontent with Congress.

The morning of the second day of the trip was spent visiting sites around Lake George, NY, including some much over looked French and Indian War sites. That afternoon sites along the upper Hudson including the site of the murder of Jane McCrea, Fort Edward and sites in Albany.

Early Sunday morning, a quick trip to the Bennington Battlefield State Park was highlighted with a great personal tour by Bob Hoar. The battlefield is well preserved and interpreted. Bob also shared some of his research into reinterpreting the battlefield using first person accounts and the landscape. Again, understanding the landscape of these places creates such a better understanding.

The majority of the day on Sunday was spent at Saratoga National Historical Park, posting several Facebook Live videos from various points across the battlefield. Also a special visit to the surrender site in Schuylerville which was recently preserved and opened as a memorial by the Friends of Saratoga Battlefield. A great preservation victory that adds to the overall story of Saratoga.

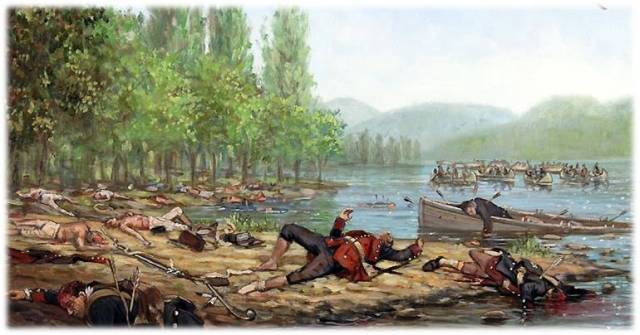

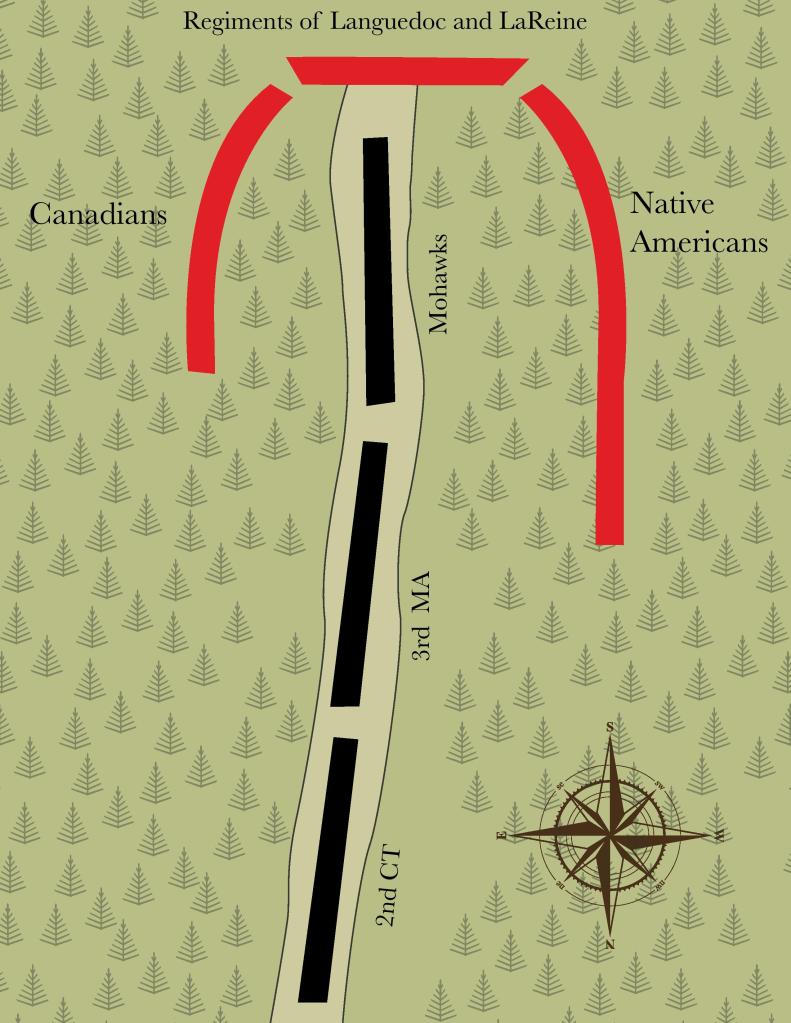

One of the highlights of the trip took place on Monday, where we received a behind the

scenes tour by Fort Ticonderoga staff. We started by learning about the military interpretive program by Ron Vido, Military Programs Supervisor. Anyone who has visited Fort Ticonderoga knows about their quality interpretive staff and programs. Ron also shared with us their plans to slowly restore the Carillon Battlefield (1758), which will be a great addition to the understanding of North America’s bloodiest battle before the Civil War. That afternoon we were treated to a behind the scenes tour of Fort Ticonderoga’s collections storage by Curator Matthew Keagle. The Fort has been collecting 18th century items for nearly 100 years. Their collection is one of the largest collection of 18th century military artifacts in the United States. From a Continental knapsack to an original copy of Baron von Steuben’s drill manual, the collection on display is only a small portion of what the museum owns. Matt also shared the museum’s ongoing work to digitize their collection for the purpose of research. The day was capped off by a visit to one of the best preserved battlefields in the United States, Hubbardton. Fought as part of the Saratoga Campaign, this is Vermont’s only battlefield. The landscape at the foot of the Green Mountains is amazing and the viewsheds are near pristine. A nice state park and visitor center are there to help explain the events of July 7, 1777.

Thank you to all the people that assisted us in this trip and all the sites that were nice enough to host us. We will be posting more on the blog in the future focusing on some of the stories around these amazing sites. Again, we encourage you to take the time to visit all these places. History books are great, but there is no substitute for being in the footsteps of history

To check out the Facebook Live videos and photos from the trip, please visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/emergingrevwar/ .