Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Michael Aubrecht

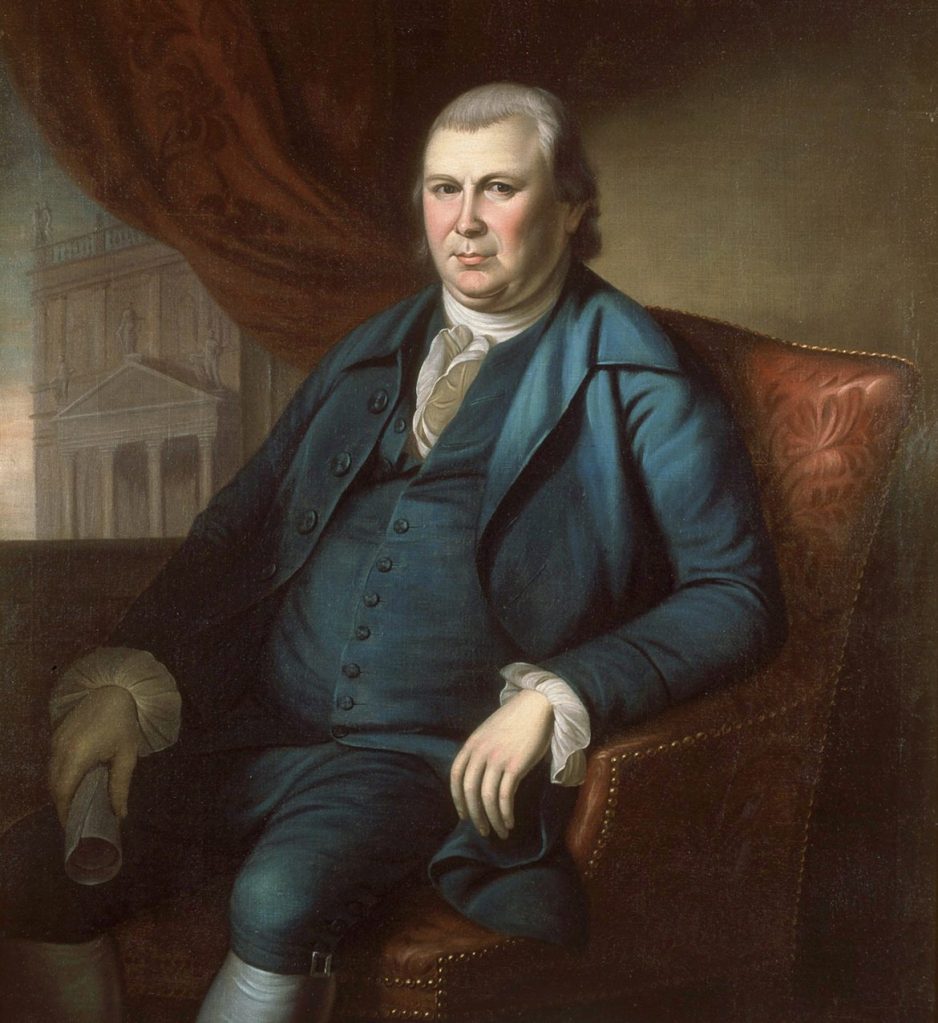

To call Robert Morris “a political renaissance man” would be an understatement. He was vice president of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety (1775–76) and was a member of the Continental Congress (1775–78) as well as a member of the Pennsylvania legislature (1778–79, 1780–81, 1785–86). Morris practically controlled the financial operations of the Revolutionary War from 1776 to 1783. He was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention (1787) and served in the U.S. Senate (1789–95). Perhaps most impressive is the fact that he signed the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation and later signed the U.S. Constitution.

At the start of the war Robert Morris was one of the wealthiest men in the colonies, but he would go on to claim bankruptcy after some catastrophic decisions. To fully appreciate the contributions of Robert Morris we must go back and examine him from the beginning.

Robert Morris was born on January 31, 1734, in Liverpool, England, the son of Robert Morris, Sr., and Elizabeth Murphet Morris. His mother died when he was only two and he was raised by his grandmother. Morris’ father immigrated to the colonies in 1700, settled in Maryland and in 1738 he began a successful career working for Foster, Cunliffe and Sons of Liverpool. His job was to purchase and ship tobacco back to England. Morris Sr. was known for his ingenuity, and he was the creator of the tobacco inspection law. He was also regarded as an inventive merchant and was the first to keep his accounts in money rather than in gallons, pounds, or yards.

In 1750 tragedy would once again strike the Morris family. In July Morris Sr. hosted a dinner party aboard one of the company’s ships. As he prepared to depart a farewell salute was fired from the ship’s cannon and wadding from the shot burst through the side of the boat and severely injured him. He died a few days later of blood poisoning on July 12, 1750. The tragedy had a terrible effect on Morris who became an orphan at the age of 16. Looking for a change he left Maryland for Philadelphia in 1748. He was taken under the wing of his father’s friend, Mr. Greenway, who filled the gap left by the death of Morris’ father. Raised with a tremendous work ethic Morris flourished as a clerk at the merchant firm of Charles Willing & Co.

Following in his father’s footsteps Morris was also gifted with successful ingenuity. In his twenties he took his earnings and joined a few friends in establishing the London Coffee House. (Today the Philadelphia Stock Exchange claims the coffee house as its origin.) Morris was sent as a ship’s captain on a trading mission to Jamaica during the Seven Years War (1756-1763). He was captured by a group of French Privateers but managed to escape to Cuba where he remained until an American ship arrived in Havana. Only then was he able to secure safe passage back to Philadelphia.

Shortly after Morris’ return to the colonies Willing retired and handed the firm over to his son Thomas who offered him a partnership. This resulted in the formation of Willing, Morris & Co. The firm boasted three ships that were dispatched to the West Indies and England importing British cargo and exporting American goods. This relationship lasted for over 40 years and was immensely successful. At one point, Morris was ranked by the Encyclopedia of American Wealth, along with Charles Carroll of Carrollton, as the two wealthiest signers of the Declaration of Independence.

As influential merchants, Morris and Willing disagreed with the changes in tax policy. In 1765, the Stamp Act was passed and was met with massive resistance. Morris was at the forefront and led protests in the streets. His fervor was so striking that he convinced the stamp collector to suspend his post and return the stamps back to their origin. The tax collector stated that if he had not complied, he feared his house would have been torn down “brick by brick.” In 1769, the partners organized the first non-importation agreement, which forever ended the slave trade in the Philadelphia region.

Morris married Mary White on March 2, 1769, and they had seven children. In 1770, he bought an eighty-acre farm on the eastern bank of the Schuylkill River where he built a home he named “The Hills.” Due to his growing reputation Morris was asked to be a warden of the port of Philadelphia. Showing his tenacity, he convinced the captain of a tea ship to return to England in 1775.

Later on, Morris was appointed to the Model Treaty Committee following Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence on June 7, 1776. The resulting treaty projected international relations based on free trade and not political alliance. The treaty was eventually taken to Paris by Benjamin Franklin who transformed it into the Treaty of Alliance which was made possible by the Continental Army’s victory at Yorktown in 1781.

Scholars disagree as to whether Morris was present on July 4 when the Declaration of Independence was approved. But when it came time to sign the Declaration on August 2 he did so. Morris boldly stated that it was “the duty of every individual to act his part in whatever station his country may call him to in hours of difficulty, danger and distress.” Until peace was achieved in 1783, Morris performed services in support of the war. His efforts earned him the moniker of “Financier of the Revolution.”

Michael is the author of “The Letters of Robert Morris: Founding Father and Revolutionary Financier.“

As I stood in Independence Hall, in the room where the Founders debated the Declaration of Independence, I suddenly started thinking of the opening scene from the musical 1776, when John Adams cries for independence while everyone else complains about either the heat or the flies. “Won’t somebody open up a window?” one of the delegates pleads. “Too many flies!” others respond, shouting him down. Adams is advocating the most lofty of ideas but everyone else is mired in their own personal discomfort. What a great metaphor.

As I stood in Independence Hall, in the room where the Founders debated the Declaration of Independence, I suddenly started thinking of the opening scene from the musical 1776, when John Adams cries for independence while everyone else complains about either the heat or the flies. “Won’t somebody open up a window?” one of the delegates pleads. “Too many flies!” others respond, shouting him down. Adams is advocating the most lofty of ideas but everyone else is mired in their own personal discomfort. What a great metaphor.

Another of the interesting components of the museum is the use of interpretive questions, including “Why were they called Hessians?” with an accompanying multi-dimensional map that shows the different German principalities that contributed troops to the British war effort. Another interesting panel discusses the first use of acronym “USA.”

Another of the interesting components of the museum is the use of interpretive questions, including “Why were they called Hessians?” with an accompanying multi-dimensional map that shows the different German principalities that contributed troops to the British war effort. Another interesting panel discusses the first use of acronym “USA.”