Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Dan Welch.

It’s December 9, 1775. Not only was the future of the fledgling Patriot’s cause at stake, but the future of our yet-to-be created Supreme Court was as well.

Over the previous months, rebel forces in the area had been engaged with Lord Dunmore’s troops for control of military supplies in the colony of Virginia. This eventually led towards the area around Norfolk, where Dunmore’s forces had fortified a position opposite a river crossing that was strategic both militarily and economically. The position, south of Norfolk, at Great Bridge, was not uncontested. Just opposite Dunmore’s stockade, known as Fort Murray, on the other side of the river, rebel forces settled in, arriving on December 2.

Col. William Wofford, in command of the 2nd Virginia Regiment and about 100 men of the Culpeper Minutemen battalion, began entrenching their position opposite Fort Murray while more militia from surrounding Virginia counties and North Carolina marched towards their aid. As more men arrived, as well as several pieces of field artillery, Lord Dunmore grew wary. He believed his only course of action was to attack Wofford’s men and drive them from the field. The attack was set to begin by dawn’s early light on December 9, 1775.

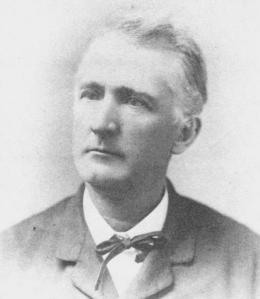

Found in the ranks of Wofford’s command that morning as the battle opened was a father and son, Thomas and John Marshall. Thomas, a vestryman, High Sheriff, and a member of the House of Burgesses had brought his son with him into the patriot ranks from Fauquier County. By the time of the battle, Thomas, who had been active in the organizing and raising the Culpeper Minutemen, had been appointed its major. His son John, age 20, its first lieutenant.

John Marshall’s biographer later recounted the importance of this moment on the young nineteen-year-old, writing “The young soldier in this brief time saw a flash of the great truth that liberty can be made a reality and then possessed only by men who are strong, courageous, unselfish, and wise enough to act unitedly…He began to discern, though vaguely as yet, the supreme need of the organization of democracy.”

John Marshall went on to serve as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court in 1801. Marshall remained at the post for thirty-four years, and, during his tenure, the Marshall Court brought the role of the Supreme Court to the fore, issued more than 1,000 decisions, and set the precedent of handing down a single majority opinion. These accomplishments and influences are just some of many that Marshall had on the Court, the federal government, and American history. Today, on the 245th anniversary of the battle of Great Bridge, it’s interesting to pause, reflect, and wonder how very different the United States and the Supreme Court might have been had Colonel Wofford’s forces, among them John Marshall, been defeated that day at the “second Bunker’s Hill affair….”

Pictures of Great Bridge Battlefield and monuments.

announce that we are partnering with Gadsby’s Tavern Museum and The Lyceum of Alexandria, VA to bring to you a day long Symposium focusing on the American Revolution.

announce that we are partnering with Gadsby’s Tavern Museum and The Lyceum of Alexandria, VA to bring to you a day long Symposium focusing on the American Revolution.