Join us this Sunday, January 11th at 7pm as we welcome back historian Patrick Hannum as we discuss the events in Virginia after the Battle of Great Bridge. The results of the British loss at Great Bridge had profound impacts on Dunmore’s plans in Virginia which led to the destruction of Virginia’s largest city. Was Norfolk burned by Dunmore as has been popularly understood or is the story more complicated? What became of the former slaves that joined Dunmore’s army? Tune in and learn about the events in Virginia in the winter 1775 – spring 1776. This Revelry is pre-recorded and will be posted to our Facebook page on Jan. 11 at 7pm and also to our You Tube and Spotify channels.

Category: Slavery

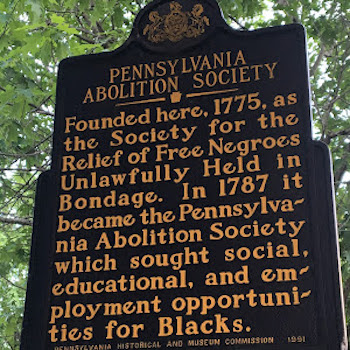

The Untold Story of America’s First Abolitionist Society – 250th Anniversary of the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage

As we approach the 250th anniversary of Lexington and Concord, on April 14, 2025 another 250th anniversary is taking place but one that is much overlooked. When we think about the fight to end slavery in the United States, names like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and William Lloyd Garrison often come to mind. But America’s organized abolitionist movement actually began decades earlier—with a quiet but powerful group of reformers in Philadelphia.

In 1775 the American colonies were on the verge of war with Great Britain, calling for freedom and independence. But even as they demanded liberty, many Americans—including some of the nation’s founders—continued to own slaves. Amid this contradiction, a small group of Philadelphia Quakers stepped up to challenge the injustice of slavery. On April 14, 1775 in Philadelphia, they formed what would become the first formal abolitionist organization in America, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage.

The name was long, but its mission was clear. This group was determined to help free Black people who were illegally enslaved or kidnapped into bondage. Their founding was quiet, overshadowed by the Revolutionary War, but it planted the seeds of a movement that would eventually reshape the nation.

At the heart of the Society were the Quakers (17 of the original 24 members were Quakers) formally known as the Religious Society of Friends. Quakers believed deeply in the equality of all people and had long spoken out against slavery. Many had already freed the people they once enslaved, and by the mid-1700s, anti-slavery had become central to their faith.

So in April 1775, a group of these Quakers, joined by a few like-minded allies, came together to create the Society. Their initial goal was modest but critical: to protect the rights of free Black people and prevent them from being illegally sold into slavery. This was not uncommon at the time, especially in cities like Philadelphia where Black communities—both free and slave—lived side by side. However, the outbreak of war later that year put much of the Society’s early work on hold. But their mission didn’t die.

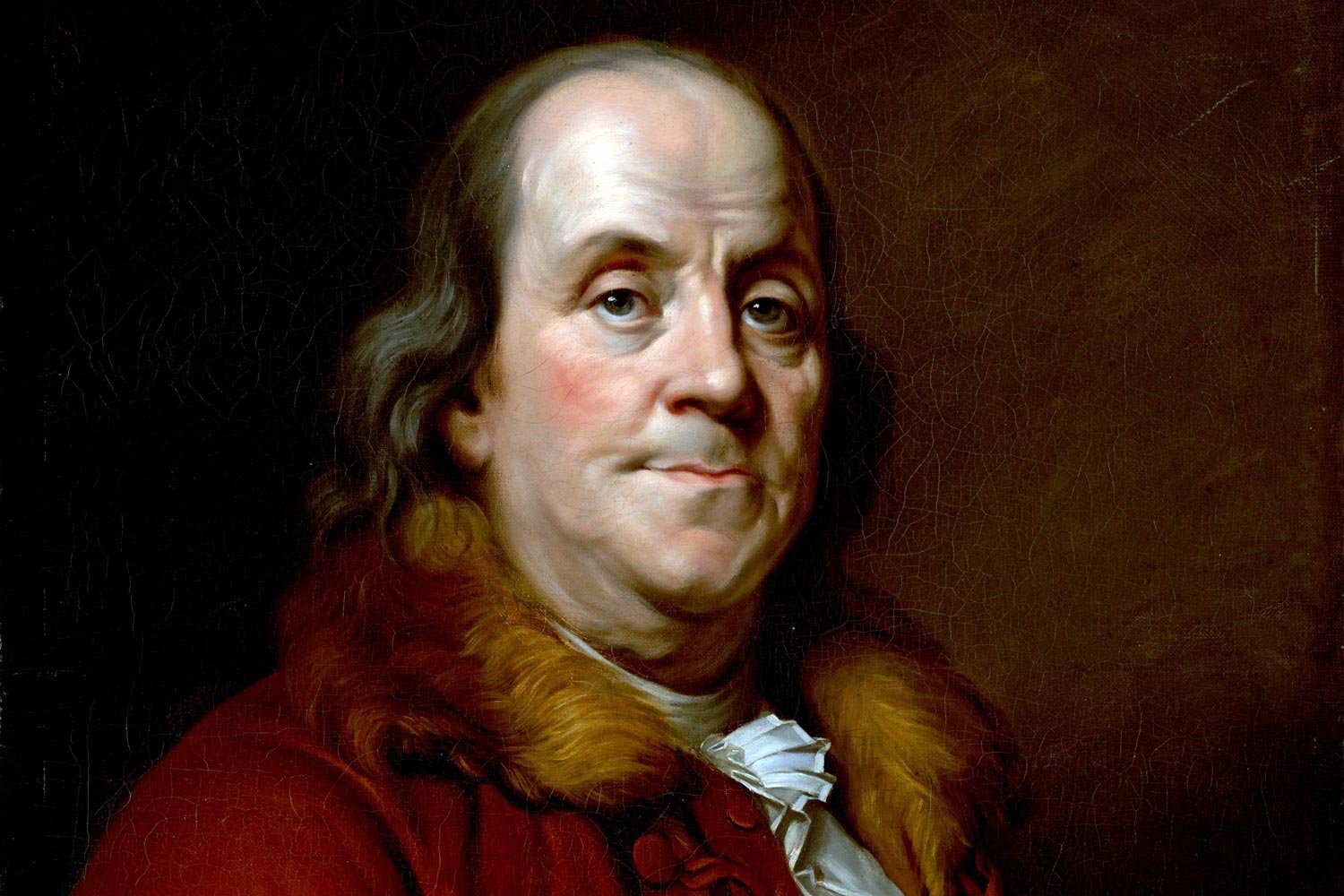

After the war, in 1784, the Society was revived with renewed energy and purpose. It was renamed the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage—still a mouthful, but a more expansive vision. Benjamin Franklin, one of America’s most celebrated founding fathers, became the Society’s president in 1787. Franklin had once owned slaves himself, but his views evolved over time. By the end of his life, he was a vocal critic of slavery and used his influence to support the Society’s goals.

This time, they weren’t just focused on defending free Black people—they were actively working to end slavery altogether. Their efforts were both legal and educational. The Society hired lawyers to defend kidnapped individuals, lobbied lawmakers, and even began promoting schools for Black children.

The Society’s work helped inspire real change. Pennsylvania became the first state to pass a gradual abolition law in 1780, a huge step forward. While the Society didn’t write the law, many of its members pushed hard for its passage and later worked to ensure it was enforced.

Still, the road was far from easy. The Society operated in a world where slavery was deeply entrenched—not just economically, but socially and politically. In the South, slavery was expanding. Even in the North, racism was widespread, and support for abolition was often lukewarm.

Despite these challenges, the Society’s model paved the way for the much larger abolitionist movements of the 19th century. It showed that legal advocacy, public education, and grassroots organizing could make a difference. It also helped define Philadelphia as a hub of anti-slavery activism that would later become home to figures like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth.

Rev War Revelry: Women of the Revolution with Saratoga Historian Lauren Roberts

Join us this Sunday at 7 pm as we welcome Saratoga historian Lauren Roberts. Lauren will discuss with us the upcoming as we discuss their upcoming Women in War Symposium and Bus Tour hosted by the Saratoga County 250th Commission. The third Annual Women in War Symposium will be held on May 4, from 8:15 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. at the Old Saratoga American Legion Post, located at 6 Clancy St. As an enhancement to the Symposium, a bus tour of historic sites will be offered on May 5.

Lauren will also discuss some of the topics being covered at the Symposium and some of the diverse history in Saratoga that relates to the American Revolution. We all know about the Battle of Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights, but how many know about the “witch of Saratoga”? Grab a drink and join us this Sunday night at 7pm on our Facebook page for a fun and insightful discussion into the great work that Saratoga County is doing to commemorate “America’s Turning Point.”

Rev War Revelry: “For Britannia’s Glory and Wealth” with Author and Historian Glenn Williams, PhD

Join us this Sunday night at 7pm as we welcome Glenn F. Williams, PhD to our popular Sunday night Rev War Revelry! Glenn will examine the political and economic causes of the American Revolution beginning at the end of the Seven Years War / French and Indian War through the resistance movements. He will dispel or clarify some of the popular beliefs about the grievances that eventually led the thirteen colonies to break with the Mother Country. This will be a timely discussion as we approach the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. Glenn Williams is a retired U.S. Army officer that until recently also enjoyed a “second career” as a military historian. He retired as a senior Historian after 18 years at the U.S. Army Center of Military History and 3 1/2 years as the historian of the American Battlefield Protection Program of the U.S. National Park Service.

Grab your favorite drink and tune in, we will be live so feel free to drop your questions in the live chat. If you are not able to tune in on Sunday, the video will be placed on our You Tube and podcast channels.

Financial Assistance for a Veteran

Peter Kiteridge was born into slavery in Boston, Massachusetts and worked in the household of the Kittredge family, from Andover, Massachusetts. Although slavery is most often associated with the southern colonies, and later the southern states, it was an established institution across the the thirteen original colonies at the time of the American Revolution. Despite being born into the institution legalized in the colony in which he lived, African American Peter Kiteredge cast his lot with those fighting for the cause of independence. The Kitteridge family had as well. Many in the extended family of Kittredges were physicians, and Dr. Thomas Kittredge went on to serve as as surgeon for Colonel James Frye’s regiment (Essex County Regiment) that was raised in Andover. In May 1775, the regiment became part of the Army of Observation. During the war, Peter Kittredge served in Captain William H. Ballard’s company of Colonel James Frye’s regiment. Peter joined the army in 1775 or 1776, according to his memory over thirty years later, and served for five years in the army before later becoming a sailor.

Read more: Financial Assistance for a VeteranBy the early 1800s, Peter Kiteridge was struggling both with his finances and his health. In this letter dated April 26, 1806, he noted that he is a freeman and in need of financial assistance. This document reveals much more about Peter, including the time between when he was a slave and when he went into military service. But the heart of Kiteridge’s letter was his request for assistance from the Selectmen of the town of Medfield. Due to a “complaint” that he had suffered since the war, perhaps the lingering effects of a disease contracted during his time in the service, Peter was unable to continue to work, and he asked for help to support his wife and four children. Because he later signed this petition with an “X” we can assume that his years as a slave left him illiterate. By the turn of the century, however, he was not the only veteran of the Revolutionary War that needed financial assistance. As this generation of servicemen aged, a growing demand for what later became known as veteran pensions increased. Today, veteran pension records, and petitions for assistance such as this, provide scholars a wealth of information on those that lived and served during this turbulent period.

Below you will find the full petition of the Medfield Selectman of April 26, 1806 courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Collection.

“Gentlemen

I beg leave to state to you my necessitous circumstances, that through your intervention I may obtain that succour, which suffering humanity ever requires. Borne of African parents & as I apprehend in Boston, from whence while an infant I was removed to Rowley and from thence again to Andover into the family of Doct. [Thom] Kiteridge, with whom as was then the lot of my unfortunate race, I passed the best part of my life as a slave. [struck: At the age of twenty five] In the year of our Lord 1775 or 6 & in the twenty fifth of my age I entered into the service of the U.S. as a private soldier where I continued five years [inserted: and] where I contracted a complaint from which I have suffered in a greater or less degree ever since & with which I am now afflicted. After leaving the army to become a sailor for two years; when I quited the sea & resided for some time in Newtown, from whence I went to Natick where I remained for a short time & then removed to Dover where I [struck: remained] [inserted: carried] as a day labourer during the period of seven years. Eight years past I removed to the place where I now live, & have untill this time, by my labor, assisted by the kindness of the neighbouring inhabitants been enabled to support myself and family. At present having arrived [2] at the fifty eight year of my life and afflicted with severe and as I apprehend with incurable diseases whereby the labour of my hands is wholly cut off, and with it the only means of my support. – My family at this time consists of a wife and [struck: three] four children, three of whome are so young as to be unable to support themselves and the time of their mother [struck: has] is wholy occupied in taking cair [sic] of myself & our little ones – thus gentlemen, in this my extremity I am induced to call on you for assistance; not in the character of an inhabitant of the town of Westfield, for I have no such claim, but as a stranger accidently fallen within your borders, one who has not the means of subsistence, & in fact, one, who must fail through want & disease unless sustained by the fostering hand of your care.

I am Gentlemen your mos obedient, most humble servant.

Peter Kiteredge

His X Mark

Attent. Ebenezer Clark

Paul Hifner

To the policemen Selectmen of the

Town of Medfield.

[docket]

Medfield 26 April 1806

[docket]

Peter Kittridge

application –

[address]

To the gentlemen Select

[Men] of the Town of

Medfield – “

On Ending Slavery: George Washington to John Mercer

Sitting down to write on September 9, 1786 from Mount Vernon, George Washington addresses his letter to Virginian, veteran of the late revolution, and plantation owner John Francis Mercer. Mercer’s family had strong ties to Virginia and the Washington family, John’s father was Washington’s attorney for many years during the eighteenth-century. Even though John had married, moved, and settled in Maryland, the two continued to correspond, although this most recent response by Washington took much longer usual. When Mercer’s letter arrived to Mount Vernon several weeks earlier, Washington was able to do little as he was fighting a “fever.” Now, he sat down to reply, and although there were many topics on his mind in which he wished to discuss with Mercer, Washington’s feelings toward slavery were first on his mind.

Read more: On Ending Slavery: George Washington to John MercerAt the time Washington composed his thoughts to Mercer, particularly on his plan to never purchase another slave, Washington owned approximately 277 slaves. Yet, he expressed his desire to slavery abolished through the gradual abolition of slavery. Washington was a man of principle, displayed time and again during the war, and his aversion to the institution only grew as Washington the man grew as well. And, his was not alone. Many founders of era, including many from the upper South, looked for gradual solutions to ending the institution, despite the modern historical narrative. In the end, Washington ensured the emancipation of his slaves following his wife’s death in his will.

Mount Vernon 9th. Sep 1786

Dear Sir,

Your favor of the 20th. ulto. did not reach me till about the first inst. – It found me in a fever, from which I am now but sufficiently recovered to attend to business. – I mention this to shew that I had it not in my power to give an answer to your propositions sooner. –

With respect to the first. I never mean (unless some particular circumstances should compel me to it) to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by, [inserted: The Legislature by] which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptable degrees. – With respect to the 2d., I never did, nor never intend to purchase a military certificate; – I see no difference it makes with you (if it is one of the funds allotted for the discharge of my claim) who the the purchaser is [2] is. – If the depreciation is 3 for 1 only, you will have it in your power whilst you are at the receipt of Custom – Richmond – where it is said the great regulator of this business (Greaves) resides, to convert them into specie at that rate. – If the difference is more, there would be no propriety, if I inclined to deal in them at all, in my taking them at that exchange.

I shall rely on your promise of Two hundred pounds in five Weeks from the date of your letter. – It will enable me to pay the work men which have been employed abt. this house all the Spring & Summer, (some of whom are here still). – But there are two debts which press hard upon me. One of which, if there is no other resource, I must sell land or negroes to discharge. – It is owing to Govr. Clinton of New York, who was so obliging as to borrow, & become my security for £2500 to answer some calls of mine. – This sum was to be returned in twelve [3] twelve months from the conclusion of the Peace. – For the remains of it [struck: this sum], about Eight hundred pounds york Cy. I am now paying an interest of Seven prCt.; but the high interest (tho’ more than any estate can bear) I should not regard, if my credit was not at stake to comply with the conditions of the loan. – The other debt tho’ I know the person to whom it is due wants it, and I am equally anxious to pay it, might be put of a while longer. – This sum is larger than the other

I am. Dr Sir

Yr. Most Obedt. Hble Sert

Go: Washington

(Letter courtesy the Gilder Lehrman Collection)

Captain James Willing’s Mississippi Raid, Part 2

Willing’s next target was the town of Manchack upon which he descended “so rapidly that they reached the Settlements without being discovered.”[1] On the 23rd, Willing’s advance parties captured the 250-ton British sloop Rebecca, with sixteen 4-pounders and six swivels.[2] It was a coup worthy of Navy SEALS. Rebecca was normally a merchant vessel, but had been armed and sent upriver to contest the Rattletrap’s advance by protecting Manchack. Instead, her presence had strengthened Willing’s force. Captured while lying against the levy opposite the town, she only had fifteen men aboard when an equal or superior force of Americans struck about 7 am.[3] With Manchack captured and the Rebecca renamed the Morris, Willing turned his attention to the end game at New Orleans, where he hoped to dispose of his booty and obtain supplies useful for the American war effort.

At New Orleans, the Congressional Agent, Oliver Pollock, was aware of Rattletrap’s advance and began making preparations to dispose of the property Willing and his raiders had taken, a growing portion of which constituted slaves. He organized a small force under his nephew, Thomas Pollock, to go up river and help Willing bring his vessels and cargo into port. Instead, Pollock and his men proceeded down the river, where they captured an English brig, the Neptune, eventually bringing her into New Orleans as a prize.[4] (The British would argue strenuously that Neptune and a private boat were not in fact legal prizes.)

Continue reading “Captain James Willing’s Mississippi Raid, Part 2”

Captain James Willing’s Mississippi Raid, Part 1

In 1778, Captain James Willing and his crew sailed and rowed the bateaux Rattletrap down the Ohio River to the Mississippi. A “left” turn of sorts then took them down the Mississippi all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. Willing’s purpose was straightforward: secure the neutrality of residents along the Mississippi, obtain supplies from New Orleans, and return them to the new United States. It was as tall an order as the Ohio and Mississippi were dangerous. British rangers and their Native American allies closely watched both shores and would readily attack vulnerable river traffic. Willing’s only refuge lay in a string of forts the Americans had established on the Ohio, but they did not extend very far. He would have to make due with his crew and the two swivel guns that armed Rattletrap. Continue reading “Captain James Willing’s Mississippi Raid, Part 1”

African American Experiences in the Siege of Ninety-Six

There are important stories often hidden in the threads of our American history. It won’t be a surprise to many that these stories desperately need to come to light. But sometimes research is scarce, with limited or hard-to-find resources to fully tell these stories to their fullest. One such example are the stories of the enslaved and free African-American people who helped build the nation, starting back even before the colonies fought for independence. America’s fight for freedom from Britain is oxymoronic considering an entire population of blacks were still kept in chains after the war. But their contributions to that fight should not go unnoticed.

The history of the construction of the British defense fortifications, including the Star Fort, at Ninety Six, South Carolina, has many layers of these diverse stories that make up the fabric of the site’s history. Lt. Colonel Nisbet Balfour set up an outpost at Ninety Six after the fall of Charleston in early 1780. In terms of fortifications – specifically the stockades and protections around the town and the jail – during this initial occupation, Balfour wrote to Cornwallis on June 24, 1780, “As to this post, it is so situated, that three small redoubts, well Abbattis [sic], I think, can easily defend it…”

Balfour also encouraged using slave labor, stating that “we have carpenters enough, and ammunition.” Balfour’s plan to construct fortifications was similar to a more extensive defense system suggested by Patrick Ferguson in his “Plan for Securing the Province of So. Carolina, &c.” dated May 16, 1780. Ferguson also recommended using slaves to construct the fortifications.

In fact, in that same June 24 letter to Cornwallis, Balfour writes that most of the labor that was used to construct the Ninety Six fortifications was from roughly 200 enslaved blacks that the British took from area plantations. Who were these 200 men? Were they promised freedom in exchange for their labor? We may never know. While research is underway to uncover the stories of these 200 individuals, very little primary resources remain. But we can still acknowledge that the British defense of Ninety Six relied heavily on the forced labor of these black men.

Work continued into the fall and winter of 1780 on the defense structures at Ninety Six, this time under Lt. Colonel John Harris Curger, including several field fortifications called abatis: defensive obstacles formed by felled trees with sharpened branches facing the enemy. The trunks are put deep into the ground, usually 4-5 feet, and is typically hard manual labor in the hard red clay of South Carolina. In a letter on December 29, 1780, Lt. Colonel Isaac Allen wrote to Cornwallis’s aide, Lt. Henry Haldane, of the hard work of the men constructing the abatis. And yes, those men were enslaved men. “I… have orderd [sic] the Abattiss [sic] cut, but Kings work like Church work goes on slow. The Poor naked Blacks can do but little this cold weather.”

Next up in the defense plan was the Star Fort itself, a large earthen redoubt whose remains are still the best-preserved earthen fort from the American Revolution. Once again, those approximately 200 enslaved men were used in its construction. Upon the completion of the fort, additional work included a network of ditches and trenches both for communication and transport of supplies.

By spring of 1781, the defenses were ready. Lt Colonel Cruger’s military force was nearly 600 but this was supplemented by a large number of Loyalist civilians in the town as well as several hundred enslaved African Americans from the surrounding country. Most likely, though it’s not known for sure, these were the roughly 200 men who helped build those very physical defenses.

But the hidden story of the enslaved at Ninety Six does not stop there, nor is their story solely on the shoulders of the British. During the Siege of Ninety Six in May and June of 1781, there are several instances that beg for more research. The first is from the morning of May 23, when Patriot forces had been digging trenches towards the Star Fort throughout the night. An attack by Loyalist militia from the fort pushed the Patriots back and they managed to capture not only the tools the Patriots were using, but “several Negro laborers abandoned by the Americans.” (Greene, 128)

It should come as no surprise that the Patriots were also using slave labor. James Mayson, a wealthy Patriot supporter living just a few miles from Ninety Six, described later how foraging parties were dispatched to the countryside to get food and supplies for Greene’s army, which included slaves “not earlier recruited by the British.”

As the Siege dragged on into June, there is one more hidden story that deserves additional research to discover the identities of the enslaved men who risked their lives for the British military garrisoned at the Star Fort. As the heat of the early Carolina summer sapped water supplies, Lt Colonel Cruger needed to get water from a nearby stream, Spring Branch, to keep their supply up. But Patriot marksmen were at the ready to prevent this from happening. Turning to the enslaved in their midst, a handful of them were ordered to strip out of their clothing and go at night to the stream to file buckets. They apparently succeeded. A British lieutenant by the name of Hatton would later recall that their naked bodies were indistinguishable “in the night from the fallen trees, with which the place abounded.”

These are just snippets of hidden stories at just one site of the American Revolution. And that’s only during one specific time in Ninety Six’s history; additional stories exist for both before and after the war, during the French and Indian War, and during the Regulator movement, as well as stories of enslaved Natives from the time of early settlement in the region.

How many stories are yet untold? Who were these men and women who currently remain nameless? For these stories aren’t just tidbits of historical facts – they represent real people who experienced real emotions and a real existence at the time when our nation was first figuring out what it wanted to be. The stories of black Loyalists and Patriots deserve to be told and in doing so, will add a new layer of complexity and understanding to the story of America during the Revolutionary War and beyond.

Bibliography

Government Documents

Greene, Jerome A. Historic Resource Study and Historic Structure Report, Ninety Six: A Historical Narrative. National Park Service: Denver Service Branch of Historic Preservation, 1978.

Manuscripts & Papers

Ann Arbor. University of Michigan. William L. Clements Library. Patrick Ferguson, “Plan for Securing the Province of So, Carolina, &c,” May 16, 1780.

Ann Arbor. University of Michigan. William L. Clements Library. Nathanael Greene Papers. James Mayson to Greene, May 29, 1781.

Washington. Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. British Public Record Office. Cornwallis Papers. Balfour to Comwallis, June 24, 1780. BPRO 30/11/2 (1)

Washington. Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. British Public Record Office. Amherst Papers. Thomas Anderson. “Journal of Thomas Anderson’s” 1st Delaware regiment [May 6, 1780-April 7, 1782].”

Books and Pamphlets

Haiman, Miecislaus. Kosciuszko in the American Revolution. New York: Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America, 1943. Reprint; Boston: Gregg Press, 1972.

Mackenzie, Roderick. Strictures on Lt. Col. Tarleton’s “History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America.” London: Printed for the Author, 1787.

Stedman, Charles. The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War, Volume 2. London: Printed for the Author, 1794.

Ward, Christopher. The War of the Revolution, Volume 2. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1952.

Weigley, Russell F. The Partisan War: The South Carolina Campaign of 1780-1782. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1970.

Phillis Wheatley: American Poet

The American Revolution was loaded with contradictions, perhaps none more glaring than the notion of fighting for individual liberty while slavery was so deeply embedded in the rebelling colonies. To truly understand the American Revolution, it’s necessary to wrestle with that reality. The stories of some individuals help shed light on the experience of enslaved Americans during the war.

Phillis Wheatley was born in West Africa, likely in 1753, and then imported into the British colonies in 1761. John Wheatley of Boston purchased her to assist his wife Susanna and daughter Mary as a house servant. Like many slaves, she was given the last name of her owners; her first may have come from the name of the ship that brought her across the Atlantic. Susanna and Mary noticed something in young Phillis and taught her to read and write, introducing her to the Bible and religion. She published her first poem in 1767 and the 1770 poem “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of the Celebrated Divine George Whitefield,” gave her some degree of fame.