I spent last weekend working at the Moores Creek National Battlefield 250th Event. The small National Park near Wilmington, NC had called on other rangers to assist, as parks often do for big events.

Continue reading “Embedded With The Troops at Moores Creek”Category: Uncategorized

“Remember, it is the fifth of March, a day ever to be forgotten; avenge the death of your brethren,”

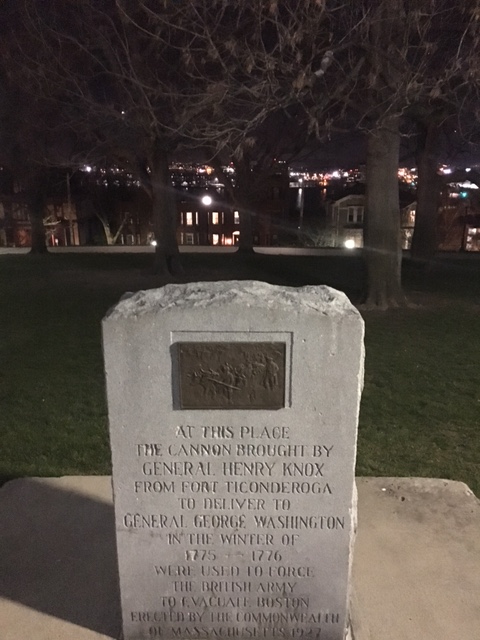

In March 1776, a quiet hill overlooking Boston Harbor became one of the first turning points of the American Revolutionary War. Dorchester Heights, rising above the southern approaches to Boston in what is now South Boston, played a decisive role in forcing the British Army to evacuate the city. The dramatic occupation and fortification of the Heights by American forces under General George Washington transformed a long, grinding siege into a strategic victory that reshaped the war’s momentum.

After the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775 and the bloody clash at Bunker Hill in June, British forces under General Thomas Gage and then William Howe found themselves effectively trapped in Boston. Surrounding militia units from Massachusetts and neighboring colonies formed a loose ring around the city, beginning what became known as the Siege of Boston. When George Washington arrived in July 1775 to take command of the newly formed Continental Army, he inherited a force that was determined but poorly supplied and short on artillery.

Throughout the fall and winter of 1775–1776, Washington searched for a way to break the stalemate. A direct assault on Boston would have been costly and risky. Instead, he looked to geography. Dorchester Heights, commanding sweeping views of the harbor and the city, offered a strategic advantage. If American forces could fortify the Heights with cannon, they would threaten both the British fleet and the troops stationed in Boston. Control of this high ground would make the British position untenable. The British Navy had encouraged British General Howe (now commanding the British forces in Boston) to take the position due to the Navy’s vulnerability if the Americans were able to command the heights with artillery. Howe underestimated the importance of the heights and also believed the Americans lacked the proper artillery and strength to hold it.

The key to Washington’s plan lay in artillery. In late 1775, Colonel Henry Knox undertook an audacious mission to transport heavy cannons captured from the British at Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York. Over the winter, Knox and his men hauled approximately 60 tons of artillery—an operation later dubbed the “Noble Train of Artillery”—over 300 miles of frozen rivers and snow-covered terrain to Cambridge, Massachusetts.

These cannons provided Washington with the firepower necessary to implement his strategy. By early March 1776, conditions were ripe. The ground was still frozen, making it easier to move heavy equipment and but would challenge their skills at building fortifications.

On the night of March 4, American troops moved silently toward Dorchester Heights. Under the cover of darkness and diversionary bombardments from other positions, they began constructing fortifications with remarkable speed. Using pre-prepared materials—fascines (bundles of sticks), chandeliers (wooden frames filled with earth), and hay bales—they built defensive works capable of withstanding British cannon fire.

By dawn on March 5, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre, British sentries were stunned to see formidable American fortifications atop the Heights, bristling with cannon aimed at the city and harbor. General Howe reportedly exclaimed that the rebels had accomplished more in one night than his army could have done in months. The strategic implications were clear. From Dorchester Heights, American artillery could rain fire down on British ships and troop positions. The Royal Navy, essential to British supply and mobility, was now vulnerable. Remaining in Boston was a risk that Admiral Molyneux Shuldham was not willing to take and pushed Howe to respond quickly.

General Howe initially planned a counterattack to dislodge the Americans. However, a fierce storm on March 6 disrupted preparations and made an amphibious assault difficult. Also, Washington got word of the planned British assault and increased his manpower on Dorchester Heights to nearly 6,000. The memory of heavy British casualties at Bunker Hill also weighed heavily. Dorchester Heights were even stronger and more defensible than Breed’s Hill had been the previous year.

Facing the prospect of severe losses and an increasingly precarious situation, Howe reconsidered. Negotiations—informal and indirect—suggested that if the British evacuated Boston without destroying the town, American forces would not attack during the withdrawal.

On March 17, 1776, British troops and Loyalists began evacuating the city. More than 11,000 soldiers and nearly 1,000 Loyalists boarded ships and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia. The Siege of Boston was over, and the city was firmly in American hands for the remainder of the war.

The occupation of Dorchester Heights marked the first major strategic victory for the Continental Army under Washington’s leadership. It demonstrated the effectiveness of coordinated planning, logistical ingenuity, and the intelligent use of terrain. Rather than launching a costly frontal assault, Washington had leveraged geography and artillery to compel the enemy’s withdrawal.

This victory also boosted American morale at a critical time. The war was far from won—indeed, it would intensify dramatically later in 1776 with British campaigns in New York—but the successful eviction of British forces from Boston showed that the Continental Army could achieve meaningful results.

Moreover, Dorchester Heights solidified Washington’s reputation as a capable commander. His cautious but decisive approach, combined with Knox’s logistical triumph, set a pattern for future operations. The event underscored the importance of high ground in military strategy, a lesson that had already been evident at Bunker Hill but was applied with even greater effect in March 1776.

Rev War Revelry: The Atlas of Independence: John Adams and the American Revolution with Dr. Chris Mackowski

Join us this Sunday at 7pm LIVE on our Facebook page as we focus on ERW’s first 2026 book release, The Atlas of Independence: John Adams and the American Revolution by Dr. Chris Mackowski. Mackowski will discuss why Adams led him to write his first “Rev War book” and the much over looked impact Adams had during the war years. We will discuss some of the more “unique” relationships Adams developed through the war time years and of course his friendship with Thomas Jefferson and his close relationship with his wife Abigail.

To order a copy of “Atlas of Independence” visit Savas Beatie’s website at: https://www.savasbeatie.com/ . Again, this will be a LIVE broadcast on our Facebook page, so grab a drink and join in on the chat!

Rev War Revelry: Henry Knox and the Noble Train

In December 1775, Henry Knox wrote to General George Washington, “I hope in 16 or 17 days to be able to present your Excellency a noble train of artillery”. However, the train of artillery would not arrive until the end of January 1776. Still an impressive feat, as Knox with his team moved 60 tons (119,000 pounds) of artillery over 300 miles from upstate New York to the environs of Boston in 70 days in the midst of winter.

This impressive feat enabled Washington to evict the British from Boston, winning the siege and giving the fledgling rebellion a victory to build momentum from.

To discuss this amazing feat and part of American military history, Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes Dr. Phillip Hamilton, a professor of history at Christopher Newport University. A historian of the American Revolutionary and Early Republican periods, he has edited and written “The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox.”

Although the program is pre-recorded, Emerging Revolutionary War hopes you still tune in on Sunday, February 22 at 7 p.m. EDT. We promise the revelry will be enlightening. If you have any questions, please drop them in the chat during the program, and we will ensure Dr. Hamilton receives them.

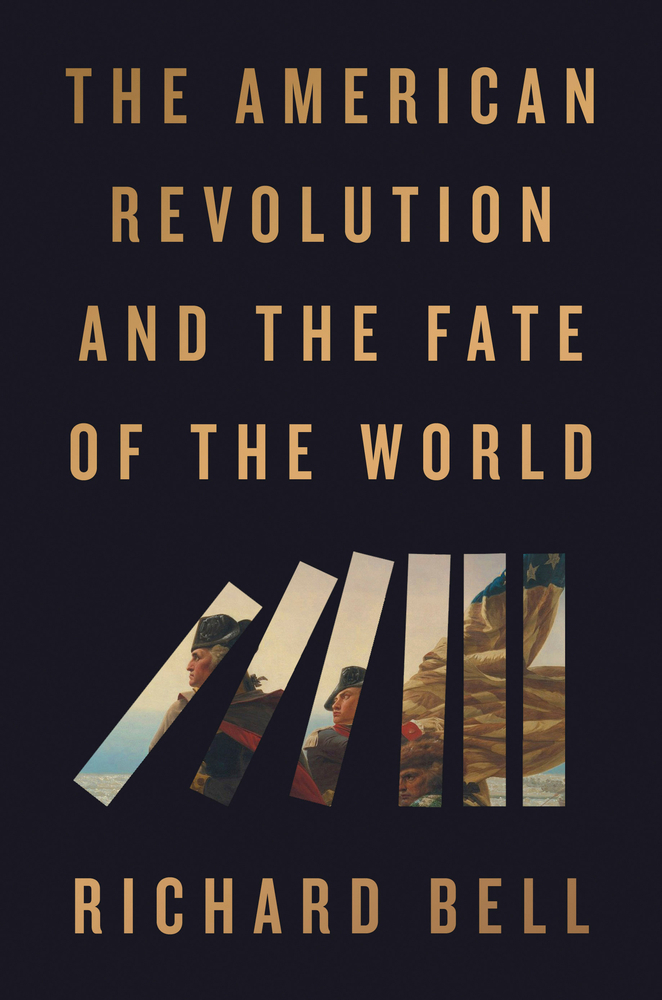

Book Review: The American Revolution and the Fate of the World by Richard Bell

Have you ever thrown a rock into a pond? The ripple effect spreads outward for quite a distance along the surface of the water. The American Revolutionary War had the same effect in the late 18th century world as that pebble did to the body of water.

Historian, author, and University of Maryland professor of history, Dr. Richard Bell, focused on those fringes with this publication, bringing them into focus and discussion that was much needed in the historiography. Indeed, this is a new must-have addition to the bookshelf of American Revolutionary Era publications. His book, The American Revolution and the Fate of the World aim to “trace the sinews of the great war from its familiar epicenter outward to all those corners of the Earth” in which the conflict affected (pg. 9). Bell’s unique background, as he describes it, being an “English-born, American trained historian” is optimal to tackling this type of endeavor. As he elaborates, he attempts—successfully this reviewer’s estimation—to peel back the “amnesia…that has its own unique form” respectively on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean when discussing the history of the American Revolution. Between the two main antagonists, Great Britain and the rebelling thirteen North American colonies, “the ways individuals and communities, then as now, are entwined” will be the central theme running like a current through his book (pg. 2).

How does Bell aim to accomplish this approach and subsequent goal? Through seven core arguments, laid out briefly here. The American Revolution “stirred the mass migration and circulation of enormous numbers of people.” Second, the cost of the war was catastrophic, and victory was not certain for the patriots but a “highly contingent result of improbable choices and last-minute improvisations.” Naval power also played “an important key to military success” and “governments, soldiers, and civilians…often acted on the understanding that trade was power. The last two core arguments, patriot “struggle for self-determination stirred imperial authorities to increase oversight and security” on their remaining controlled territories and the American Revolution “was a conflict in which the call for liberty rang around the world as never before” (pg. 10).

Does he succeed? Admirably. By taking the reader through fourteen chapters that seem to be standalone essays but instead bring subjects usually forced to the fringes of histories of the period into focus. From female personas such as Molly Brant, the great leader for indigenous independence to using Peggy Shippen as the focal point for Loyalists and the throes of the great migration that followed the patriot victory in the American Revolution. From other exalted leaders, such as Baron von Steuben and King Louis XVI of France to ordinary citizens and the enslaved, trying to improve and sustain life during the conflict.

His astute insight and impeccable research acumen brings to life William Russell a privateer that might have some of the worst luck of any that sailed the Atlantic Ocean during the war to Bell, uncovering interesting snippets such as the twisted tale of tea. Americans are most familiar with the Boston Tea Party of December 1773, but did you know that by “the early 1800s, taxes levied on the tea trade had become a vital source of US government revenue and, ironically, “became a major contributor of funds to pay the nation’s war debts” (pg. 33).

Did you ever think of the central importance of trade to war? Maintaining colonies and trade routes that kept soldiers, sailors, and citizens fed and government coffers filled? Bell rightly traces the integral connection as “cargo vessels laden with Cuban gold, Barbadian sugar, Irish meat, and Dutch munitions bound together the conflict’s several theaters just as tightly as troops transports and naval fleets…” (pg. 360).

This was a whirlwind synopsis of Bell’s seven core arguments and a sneak peek into the dept of his research and viewpoints. He has filled in the foundation of those fringes of the American Revolutionary War era history. Like those ripples from that proverbial rock, there is still more to discover that have direct ties to the defining era of the American Revolution. One example that he discusses in need of further study is “in the 250 years since 1776, rebels, separatists, and state makers on every settled continent have crafted more than a hundred declarations of independence in imitation of the American original” (pg. 361). Another ripple, started by Bell, that can be explored more fully. The fate of the world rested with the tremors started by the American Revolution, and one can argue the fate of the world still relies on those same tremors of a 21st-century variety today.

Book Information:

The American Revolution and the Fate of the World

Richard Bell

Riverhead Books (Penguin Random House, INC), New York, 406 pages with images

$35.00

Update: Rev War Revelry with Jack Kelly – 2/8/26

Due to a conflict in time with the Super Bowl this Sunday night, we will be moving the Rev War Revelry with Jack Kelly to a later date. We appreciate your understanding and will release a new date and time once confirmed. Thank you.

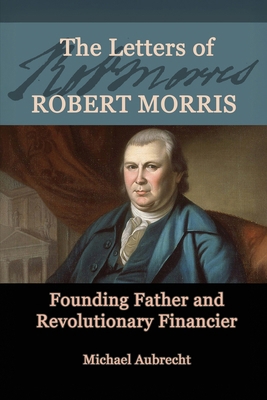

Book Review: The Letters of Robert Morris: Founding Father and Revolutionary Financier. By Michael Aubrecht

Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Evan Portman for this review.

Among the pantheon of America’s Founding Fathers, Robert Morris is a name rarely mentioned beyond circles of historians. However, Michael Aubrecht sheds light on this phantom revolutionary figure with his book The Letters of Robert Morris: Founding Father and Revolutionary Financier. His work represents the first time the primary sources of Robert Morris have been compiled in print.

The Letters of Robert Morris spans the financier’s political life from his time in the Continental Congress to his time in debtors’ prison at the turn of the eighteenth century. Morris’s correspondence provides a fascinating window into his public life. His recipients often include the likes of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton. Some of Morris’s most fascinating correspondence comes from late 1776 and early 1777, during which the financier provided Washington’s army with much needed supplies. His letters to Washington during the Ten Crucial Days reveal the anxiety and trepidation that pervaded the fledgling United States at that time.

Also compelling is Morris’s role in establishing the Bank of North America and a new national currency, which he outlined to a letter to John Hanson, the president of Congress, in 1782. His frequent exchanges with individuals like Hamilton and Franklin about the bank and its expenditures highlight Morris’s financial acumen but also how much of his own personal wealth he was willing to pledge to the American revolutionary cause.

Overall, Aubrecht’s editorial approach is sound and tactful. He adapts hundreds of Morris’s letters the National Archives’ online repository. While many of these letters are accessible on the internet, there is particular value in assembling them in print as Aubrecht has. While an online repository can sometimes feel disjointed, a printed volume can help readers to make connections and allow the editor to exert a bit more influence over the narrative.

However, Aubrecht places Morris’s voice at the center of this volume, intruding little on the language and meaning of the original texts. Aubrecht occasionally inserts a missing word or clarifies a misspelling, but his methodology essentially allows Morris to speak for himself. Aubrecht also provides useful biographical information on his subject in the introduction as well as advocates for his importance as one of the Revolution’s most prominent financiers.

The collection could, however, benefit from a bit more contextual information, particularly in between substantial time gaps between letters. While most readers need no introduction to many of Morris’s illustrious correspondents, a brief paragraph providing the context of a set of letters could prove useful in providing a more detailed picture of Morris’s life. The collection could also make more liberal use of footnotes in defining key terms and antiquated language, as well as elaborating on some of the lesser-known people Morris mentions in his correspondence.

Regardless, The Letters of Robert Morris is a welcome contribution to the existing literature on one of America’s underappreciated Founding Fathers. Aubrecht’s selection proves to be a key asset to researchers and history buffs alike.

Information:

The Letters of Robert Morris: Founding Father and Revolutionary Financier. By Michael Aubrecht. Berwyn Heights, MD: Heritage Books, 2025. Softcover, 431 pp. $43.00.

Canadian Invasion: The Occupation of Montreal

In the fall of 1775, 250 years ago, the American Revolutionaries invaded Canada. It was hoped that a 14th colony could be added to the effort. Members of the Continental Congress felt that Canada’s majority French Catholic population was unhappy with British rule, and would welcome the chance to join them. Conquering Canada would also remove the potential for a British invasion from the north.

General Richard Montgomery led forces from New York State north, and by November 13 captured Montreal. He and most of his troops departed for Quebec on November 28, where they joined forces with General Benedict Arnold to attack that city. General David Wooster remained in command at Montreal.

The Chateau Ramezay in the center of the town became headquarters for the occupying Continental Army. In the meantime American forces were defeated at Quebec on December 31, with General Montgomery killed.

By spring, Montreal was under the command of Colonel Moses Hazen, a resident of the Province of Quebec. He tried to raise troops for the Continental army, but only about 500 joined his Canadian Regiment.

With about 10,000 people, Montreal was the fifth largest city in North America. While residents initially welcomed the Americans, they soon saw them as invaders and occupiers. Uncertainty about the economy, American intentions, and the defeat at Quebec all caused Canadians to gradually lose support for the Americans. For the Continental troops stationed here that winter, it must have been a dreary, cold, and depressing experience.

View of Montreal and its Walls in 1760. Image Source: Pictorial Field-Book of the American Revolution by Benson Lossing (1860).

On April 29, 1776 a delegation from the Continental Congress arrived, which included Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Chase, Charles Carroll, and Carroll’s cousin, John Carroll, Catholic priest. It was hoped that a priest would give the American cause more legitimacy with the Canadians. Upon arriving, General Arnold had his troops salute the Congressional delegation.

Charles Carroll wrote, “On our landing, we were welcomed by General Arnold in the most courteous and friendly manner and conducted to the headquarters where a society of women and gentlemen of distinction had assembled. As we were on our way from our landing site to the General’s house, the cannon of the citadel thundered in our honour as commissioners of the Congress.”

It was all a failure. The Canadians were unwilling to throw off British rule, which guaranteed religious freedom and protection of their language and culture. On May 11, 1776, Franklin departed, saying it would have been easier if the Americans had tried to buy Canada than invade it.

Arnold and his troops occupied Montreal until June 15, when British forces advancing from Québec forced their evacuation. For seven months, the largest town in Canada was under American military occupation.

Today one of the few reminders of the American occupation is the Chateau Ramezay, built in 1705. It had been the Governor’s mansion during British rule and was the seat of Government until 1849. It is now a museum. Also visible are the old stone walls that surrounded the city. These fortifications defended the town in 1763 during the French and Indian War, and again in 1775 and 1776.

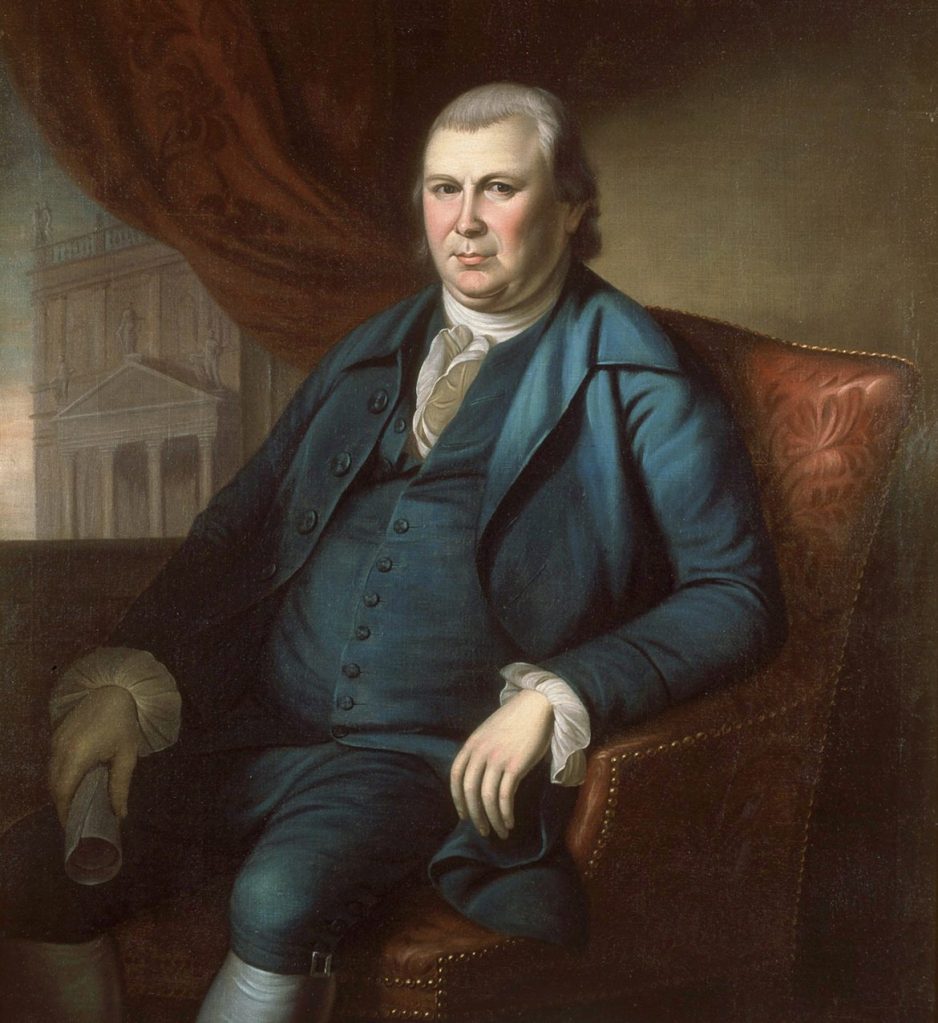

Robert Morris: Founding Father and Revolutionary Financier

Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Michael Aubrecht

To call Robert Morris “a political renaissance man” would be an understatement. He was vice president of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety (1775–76) and was a member of the Continental Congress (1775–78) as well as a member of the Pennsylvania legislature (1778–79, 1780–81, 1785–86). Morris practically controlled the financial operations of the Revolutionary War from 1776 to 1783. He was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention (1787) and served in the U.S. Senate (1789–95). Perhaps most impressive is the fact that he signed the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation and later signed the U.S. Constitution.

At the start of the war Robert Morris was one of the wealthiest men in the colonies, but he would go on to claim bankruptcy after some catastrophic decisions. To fully appreciate the contributions of Robert Morris we must go back and examine him from the beginning.

Robert Morris was born on January 31, 1734, in Liverpool, England, the son of Robert Morris, Sr., and Elizabeth Murphet Morris. His mother died when he was only two and he was raised by his grandmother. Morris’ father immigrated to the colonies in 1700, settled in Maryland and in 1738 he began a successful career working for Foster, Cunliffe and Sons of Liverpool. His job was to purchase and ship tobacco back to England. Morris Sr. was known for his ingenuity, and he was the creator of the tobacco inspection law. He was also regarded as an inventive merchant and was the first to keep his accounts in money rather than in gallons, pounds, or yards.

In 1750 tragedy would once again strike the Morris family. In July Morris Sr. hosted a dinner party aboard one of the company’s ships. As he prepared to depart a farewell salute was fired from the ship’s cannon and wadding from the shot burst through the side of the boat and severely injured him. He died a few days later of blood poisoning on July 12, 1750. The tragedy had a terrible effect on Morris who became an orphan at the age of 16. Looking for a change he left Maryland for Philadelphia in 1748. He was taken under the wing of his father’s friend, Mr. Greenway, who filled the gap left by the death of Morris’ father. Raised with a tremendous work ethic Morris flourished as a clerk at the merchant firm of Charles Willing & Co.

Following in his father’s footsteps Morris was also gifted with successful ingenuity. In his twenties he took his earnings and joined a few friends in establishing the London Coffee House. (Today the Philadelphia Stock Exchange claims the coffee house as its origin.) Morris was sent as a ship’s captain on a trading mission to Jamaica during the Seven Years War (1756-1763). He was captured by a group of French Privateers but managed to escape to Cuba where he remained until an American ship arrived in Havana. Only then was he able to secure safe passage back to Philadelphia.

Shortly after Morris’ return to the colonies Willing retired and handed the firm over to his son Thomas who offered him a partnership. This resulted in the formation of Willing, Morris & Co. The firm boasted three ships that were dispatched to the West Indies and England importing British cargo and exporting American goods. This relationship lasted for over 40 years and was immensely successful. At one point, Morris was ranked by the Encyclopedia of American Wealth, along with Charles Carroll of Carrollton, as the two wealthiest signers of the Declaration of Independence.

As influential merchants, Morris and Willing disagreed with the changes in tax policy. In 1765, the Stamp Act was passed and was met with massive resistance. Morris was at the forefront and led protests in the streets. His fervor was so striking that he convinced the stamp collector to suspend his post and return the stamps back to their origin. The tax collector stated that if he had not complied, he feared his house would have been torn down “brick by brick.” In 1769, the partners organized the first non-importation agreement, which forever ended the slave trade in the Philadelphia region.

Morris married Mary White on March 2, 1769, and they had seven children. In 1770, he bought an eighty-acre farm on the eastern bank of the Schuylkill River where he built a home he named “The Hills.” Due to his growing reputation Morris was asked to be a warden of the port of Philadelphia. Showing his tenacity, he convinced the captain of a tea ship to return to England in 1775.

Later on, Morris was appointed to the Model Treaty Committee following Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence on June 7, 1776. The resulting treaty projected international relations based on free trade and not political alliance. The treaty was eventually taken to Paris by Benjamin Franklin who transformed it into the Treaty of Alliance which was made possible by the Continental Army’s victory at Yorktown in 1781.

Scholars disagree as to whether Morris was present on July 4 when the Declaration of Independence was approved. But when it came time to sign the Declaration on August 2 he did so. Morris boldly stated that it was “the duty of every individual to act his part in whatever station his country may call him to in hours of difficulty, danger and distress.” Until peace was achieved in 1783, Morris performed services in support of the war. His efforts earned him the moniker of “Financier of the Revolution.”

Michael is the author of “The Letters of Robert Morris: Founding Father and Revolutionary Financier.“

The Adams Family Memorials in Quincy’s Merrymount Park

I want to take a moment to give a shout out to the Quincy Historical Society in Quincy, Massachusetts.

For my upcoming ERW Series book on John Adams in the Revolution, Atlas of Independence, I included an appendix that highlights a number of Adams-related sites in his hometown of Quincy: his birthplace; the home he first lived in with Abigail; his later-in-life home, Peacefield; the “Church of the Presidents,” which includes his crypt; and several other cool spots.

One of the places I direct people is to Merrymount Park, which features two monuments to Adams and members of his family. The newer of the two consists of a statue of John that stands across a small plaza from a dual statue of Abigail and a young John Quincy. The distance symbolizes the distance between John and his family for much of his public life.

Sculptor Lloyd Lillie created the Abigail and John Quincy statues first, in 1997. They stood together in downtown Quincy along Hancock Street. John was installed across from them in 2001, separated by traffic. When the city redesigned downtown and created the new Hancock-Adams Commons in 2022, the statues were relocated to Merrymount Park to join an older monument already standing there.

That older monument was a little harder to investigate.

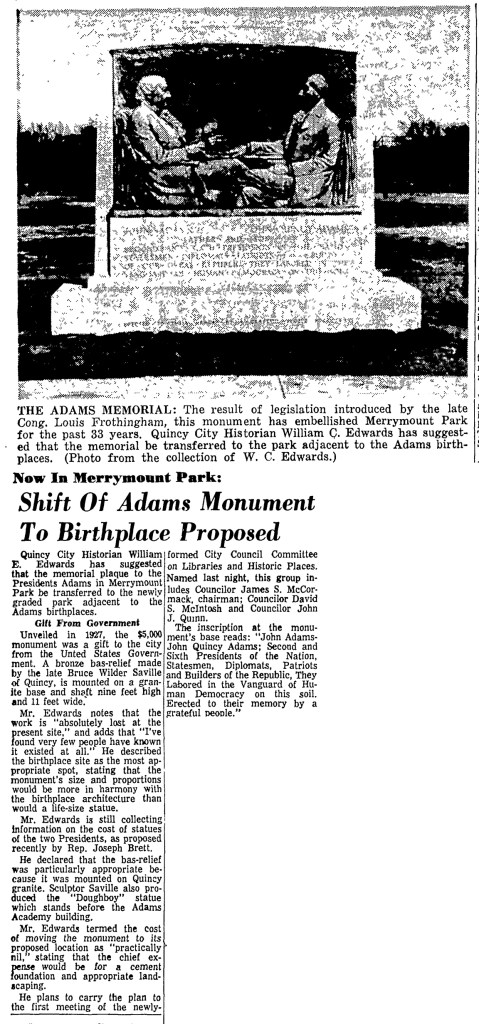

The monument itself is made from Quincy granite, a longtime staple of the local economy. A bas relief bronze tablet mounted on the granite shows John and an adult John Quincy—both as presidents—seated together for an imagined conversation with each other. An inscription reads: “Father and Son, Second and Sixth Presidents of the Nation, Statesmen, Diplomats, Patriots, and Builders of our great Republic, they labored in the vanguard of human democracy on this soil.”

Beyond that, I knew the memorial had once been moved to the site where the John and John Quincy birthplaces stand along Franklin Street, but I didn’t know when and I didn’t know when the monument came back to Merrymount. I couldn’t even find the year of the monument’s dedication or the name of the sculptor. The internet didn’t seem to know these things, and none of my reference materials referenced them.

And so it was that I reached out to the Quincy Historical Society to see if they might have anything in their archives that could help me out.

Archivist Mikayla Martin went above and beyond to assist, sending me a neat little bonanza of stuff! Since she sent me more material than I had room for in the book, I thought I’d take the opportunity to share my windfall here so that you, too, could benefit from the Quincy Historical Society’s kindness.

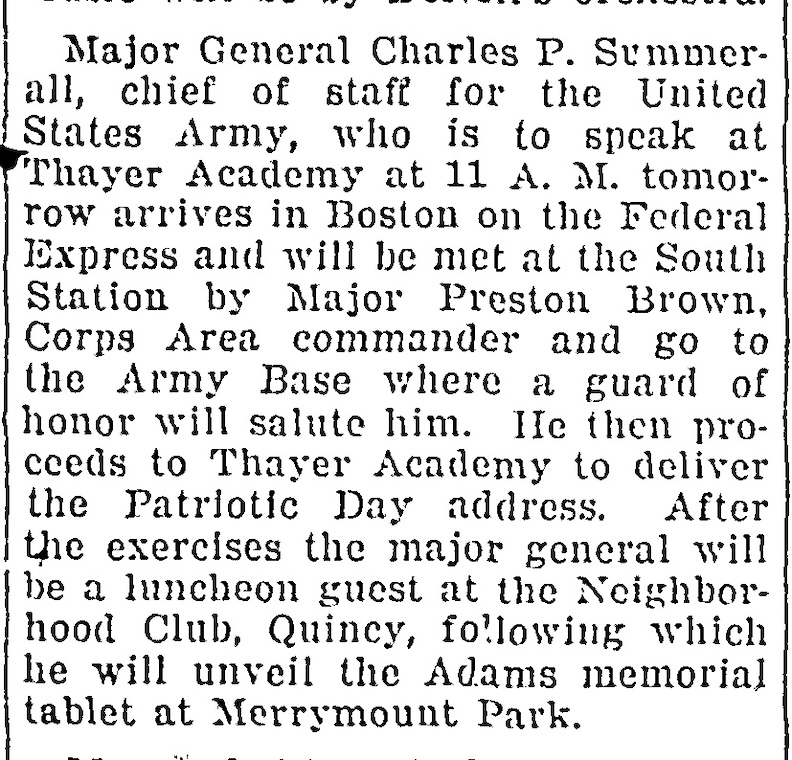

The memorial, as it turned out, was dedicated in 1927. The chief of staff of the United States Army at the time, Maj. Gen. Charles P. Summerall, served as master of ceremonies for the event, according to a clipping from the Patriot Ledger the historical society sent me:

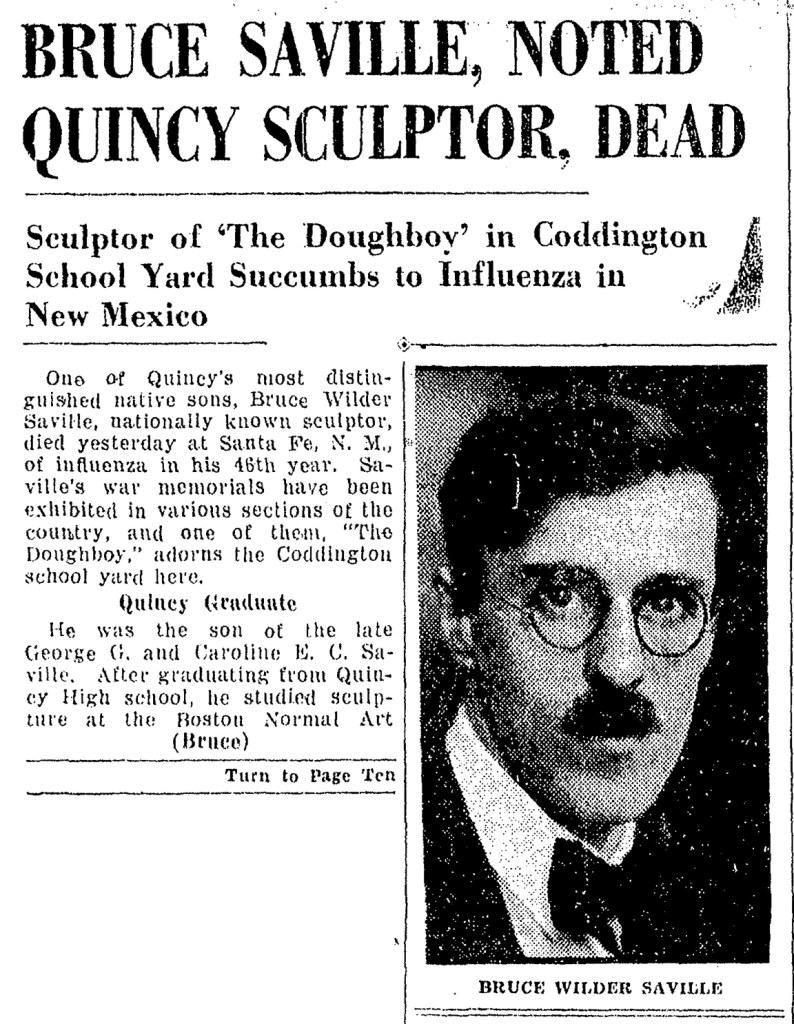

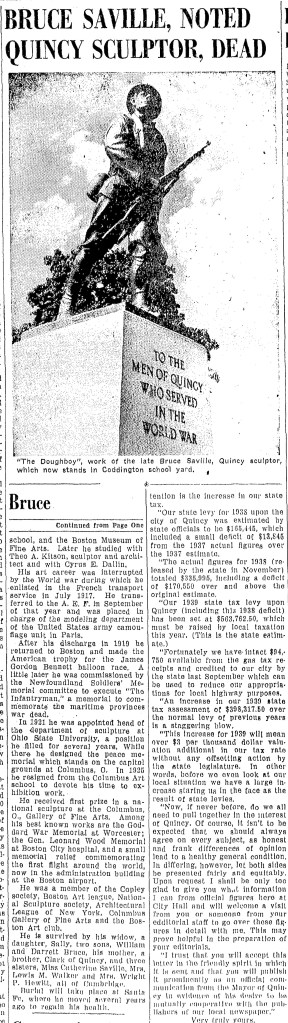

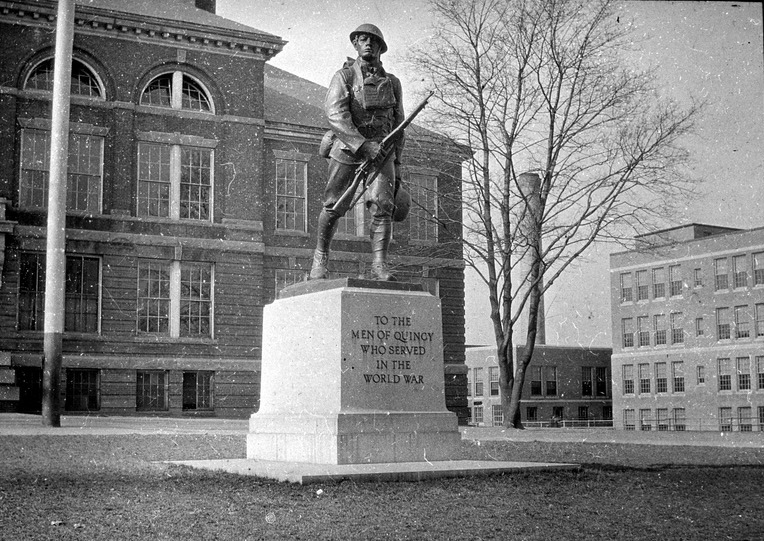

The Patriot Ledger hailed the memorial’s sculptor, Bruce Wilder Saville, as “One of Quincy’s most distinguished native sons.” Saville was best known in town for another of his works, the WWI “Doughboy” Memorial that stood in front of the Coddington School. The Quincy Historical Society included Saville’s obituary from the Patriot Ledger, which I’ll reproduce below, along with a photo of the Doughboy Memorial that the society sent me.

Another newspaper clipping revealed that the $5,000 memorial was a gift to the city of Quincy from the U.S. government. In 1961, city leaders voted to move the monument to the Adams birthplaces, but when the NPS took over management of the site 1979, the city returned the monument to Merrymount Park. I’ll reproduce a newspaper article related to that, as well (see below).

Every monument and memorial has a story of its own, and I find those stories fascinating. They can tell us a lot about the people they honor as well as the people who are doing the honoring.

Please consider supporting your own local historical society (and, if you’re so inclined, please consider supporting the Quincy Historical Society while you’re at it). Organizations like this provide invaluable services to researchers everywhere, but more importantly, they carry the torch for the history in your own back yard.